PACKED IN A LOCAL

Every day, Mumbai’s suburban trains carry

8 million people with remarkable efficiency. But the ageing and overstretched network needs an urgent overhaul

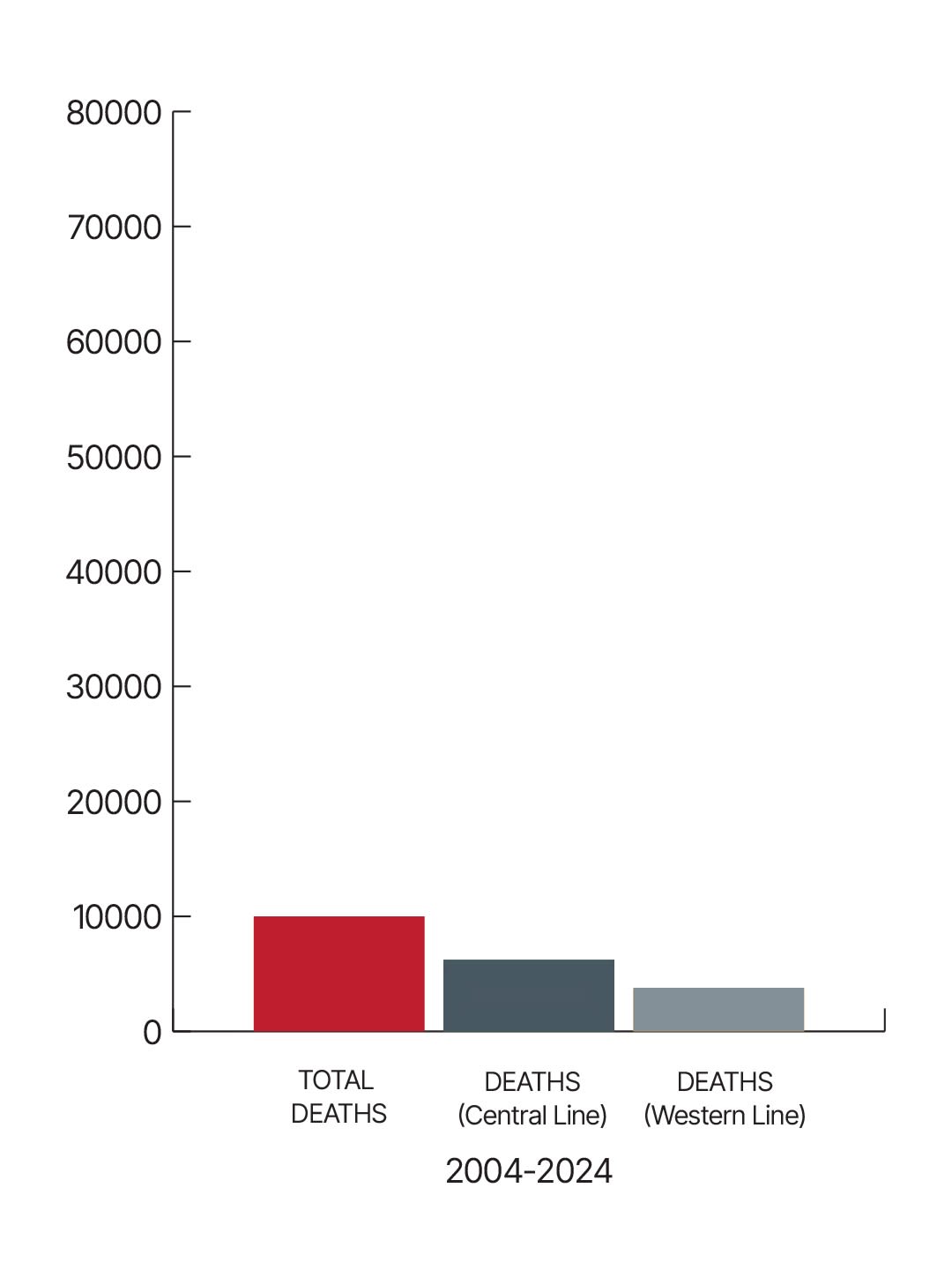

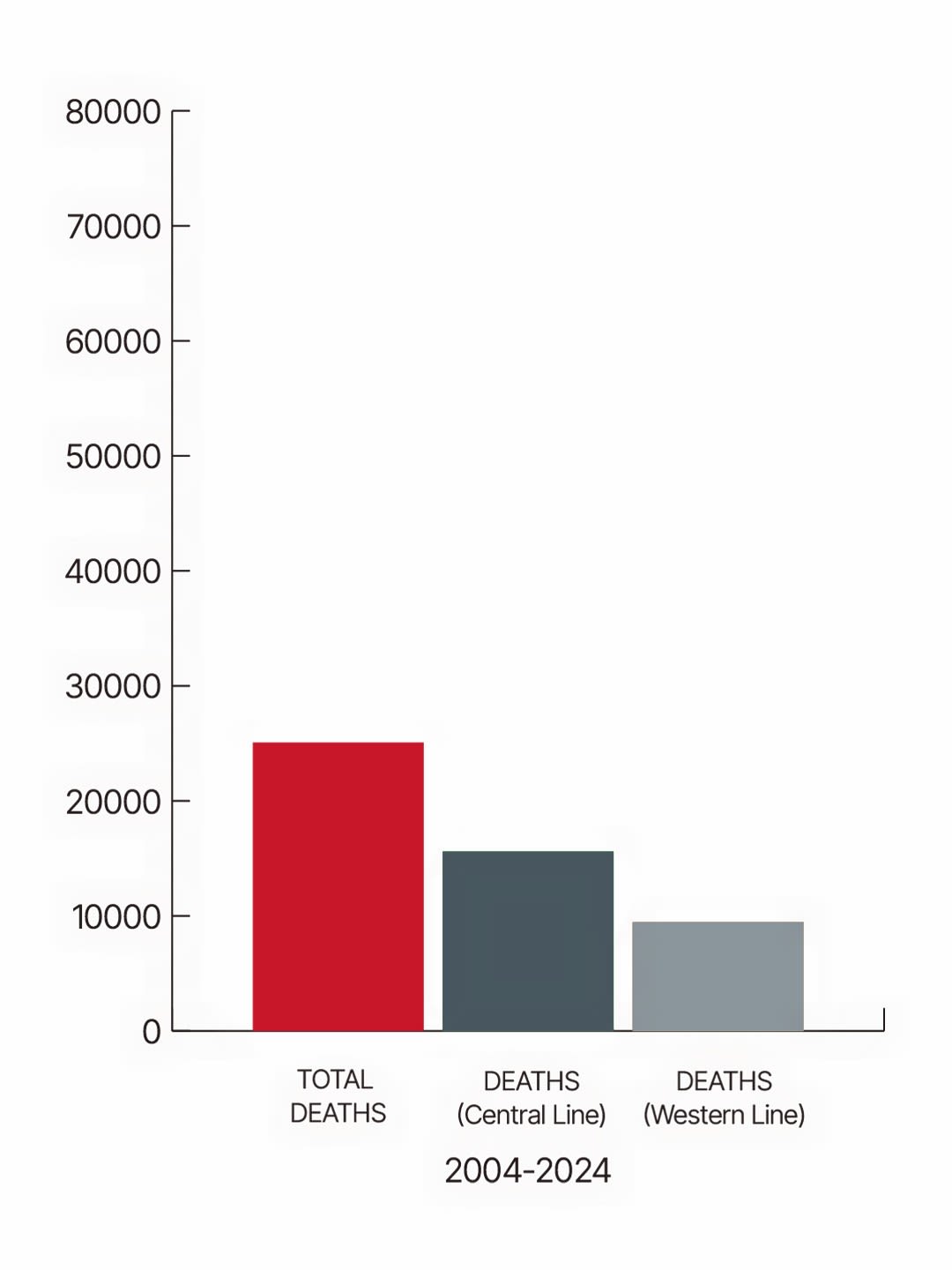

In the two decades between 2004 and 2024, Mumbai’s local trains claimed over 66,431 lives – 41,349 people on the Central Railway line and 25,082 on the Western line in accidents. In 2024 alone, there were 2,468 fatalities on the suburban network and left over 2,697 injured.

June 9 was one of those days. That day, Ketan Saroj, a 23-year-old who had recently begun working at a call centre in Airoli, boarded a local train from Shahad to CSMT (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus). Like most days, he stood on the foot rails, dangerously hanging out of the door, clinging to the side bars as the heaving crowd leaned onto him. And then, at the Mumbra curve, where two tracks converge and come dangerously close, passengers at the door of another train passing on the adjacent tracks collided with those on his train. Ketan and a few others lost their balance and fell onto the tracks. He was among the five who died in the accident that left nine injured.

“Ketan had only just started working. He was excited, hopeful. We never imagined something like this could happen so soon,” says his grieving father Dilip Saroj.

Every day, Mumbai’s suburban rail network carries around 8 million people with remarkable efficiency, linking 119 stations across 450 route-km. Part of the Indian Railways’ Central and Western Lines, the suburban network has five corridors, two operated by the Western Railways, two by the Central Railways and one on the Harbour Line of Central Railways. But this ageing city lifeline is marked by chronic overcrowding and witnesses thousands of accidents and deaths every year.

Experts say these are not freak accidents but a sign of systemic, predictable failures – trains packed beyond capacity, unsafe boarding conditions, inadequate platforms, and operational delays that ripple across the city.

Need for design upgrade

The suburban rail system has far outgrown its original design and while passenger demand has increased exponentially, infrastructure upgrades have not kept pace. Each 12-coach train is built to accommodate around 1,200 passengers, but during peak hours, the load often crosses 4,000.

The Research Designs and Standards Organisation (RDSO) prescribes a limit of eight passengers per square metre, but local trains often carry double that, with 14 to 16 passengers crammed into the same space.

This results in commuters hanging out of doors, sitting on metal couplings between compartments, and dangerously standing on footboards. A sudden jerk or bend in the line can lead to fatal consequences.

The existing coach layout allocates 60 per cent space for seating and 40 per cent for standing passengers. According to a railway official who spoke on condition of anonymity, transport experts have for long advocated a reversal of this ratio for Mumbai, a city with high density, short-distance commuter patterns. A Metro-style seating with 70 per cent standing capacity, they say, would allow for smoother flow and higher occupancy. Yet, despite several recommendations, coach design has not changed.

The existing coach layout allocates 60 per cent space for seating and 40 per cent for standing passengers. A Metro-style seating with 70 per cent standing capacity would allow for smoother

flow and higher occupancy

Shortage of rakes

The Central Railway’s stretch between Thane and Kalyan is among the most crowded. In 2024, more than half of all deaths of people falling off trains occurred in this zone — 116 at Kalyan, 68 at Thane, and 39 at Dombivli.

The corridor services areas that have grown over the decades, thanks to affordable housing schemes, but the frequency and capacity of trains have not kept pace with demand.

A decade ago, Central Railway primarily operated nine-coach trains; today, it runs 12- and 15-coach services, with 22 15-car rakes in service. The Western Railway has much more, operating over 210 15-car services. While this marks a capacity expansion, with a train now arriving every 180 seconds on the Thane-Kalyan line, the population growth in the corridor has outpaced infrastructure, leading to continuous overcrowding.

“Though there are trains every 3 to 5 minutes, we often have to wait for two or three trains before we can even board, and when we do, it is a physical battle to survive the journey. During peak hours, many board in desperation, knowing they may have to stand at the door for up to an hour,” says Prasad Magdum, a banker who travels from Dombivli to Byculla every day.

The frequency and capacity of trains have not kept pace with demand

The frequency and capacity of trains have not kept pace with demand

Introduction of AC trains

In 2020, in an attempt to modernise and increase safety, the Indian Railways introduced air-conditioned trains on Mumbai’s suburban rail network.

Under Phase 3A of the Mumbai Urban Transport Project (MUTP) – an ongoing multi-phase World Bank-supported plan to develop Mumbai’s transport infrastructure led by Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation (MRVC) – 191 AC trains are to be introduced on the suburban network in phases. At present, 258 12-coach Electric Multiple Unit or EMU trains are used to run 2,951 train services every day, out of which 30 were converted to all-AC trains.

These trains featured automatic doors, improved lighting, and better ventilation. But the plan has had unintended consequences. While these trains were meant to supplement the existing fleet, their introduction came with a reduction in non-AC trains, particularly on the Central line. This has led to fewer affordable options for second-class commuters, who make up nearly 70 per cent of Mumbai’s suburban rail passengers.

“Also, many passengers who purchase second-class tickets end up boarding AC trains illegally, often blocking the automatic doors and overloading compartments. And there are no ticket checkers seen during peak hours,” says Shreya Raut, a regular AC train commuter from Thane to CSMT.

"During peak hours, many board in desperation, knowing they may have to stand at the door for up to an hour," says Prasad Magdum, a banker

"During peak hours, many board in desperation, knowing they may have to stand at the door for up to an hour," says Prasad Magdum, a banker

Not enough shuttle services

Mumbai’s rail network carries both suburban locals and long-distance express trains, many of which run on the same tracks, often leading to operational clashes.

During peak hours, suburban trains often face delays due to the priority given to long-distance express trains. At key junctions such as Kalyan and Kurla, express trains occupy platforms and tracks, forcing suburban services to wait.

“The timetables of long-distance trains should be reworked so that local trains can move uninterrupted, at least during the peak hours, when the commuter load is the highest,” says Samir Zaveri, a railway activist and a 90% disabled individual who lost both legs in a railway accident.

Areas beyond Thane, including Badlapur, Ambernath, Kasara, and Karjat, are served by fewer trains. Many commuters from these distant towns rely on fast local services to reach the city centre, but the limited number of trains and their infrequency result in overcrowding and chaotic boarding.

“Introducing additional shuttle services on these stretches could ease pressure on mainline trains and reduce accidents due to overcrowding, especially given the fact that most of the fatal accidents take place beyond Thane,” adds Zaveri.

The segregation of suburban and long-distance traffic at Kalyan Yard was proposed to address this issue. The plan involved dedicating certain platforms and tracks for suburban trains and separating them physically from long-distance trains. This segregation would have reduced delays, avoided operational conflicts, and improved the overall punctuality of services. However, the project that started under MUTP-3 remains in its early stages.

The limited number of trains and their infrequency result in overcrowding and chaotic boarding

The limited number of trains and their infrequency result in overcrowding and chaotic boarding

A risky ride

The roughly 15-kilometre stretch between Thane and Dombivli is among the most accident-prone sections of the suburban railway, with passenger rights activists pointing to sharp curves and outdated track design, particularly between Diva, Mumbra, and Kalwa, as major hazards – also where the recent accident took place.

Advocate Deepak Dubey, who lost his brother in April 2024 on the same Diva-Mumbra stretch, says, “The railways must conduct thorough safety audits and explore modern solutions like tunnels or flyovers to replace these dangerous curves.”

According to a senior Government Railway Police official, “The Mumbra curve is particularly hazardous. Even seated passengers feel the jerk. For those standing at the door, it’s often deadly. In this case, the two trains tilted inward on the curve, and hanging passengers collided.”

Railway officials confirmed that the area has seen repeated accidents, with the risks heightened during the monsoons when the ground beneath the tracks softens, affecting track alignment. While a similar curvature near Sion was corrected in the past due to available land, Mumbra’s dense surroundings leave little room for realignment.

"We still don’t know how he fell — whether it was overcrowding, a jerk or something else. But we lost him in seconds"

Mala Dubey, mother of Avadhesh Dubey, 25. A postgraduate student of IIT Patna, he fell off the coach between Diva and the Thane railway creek

"Fellow passengers said he wasn’t even on the edge. But he fell and died on the spot."

Neeta Doshi, mother of Ayush Doshi, 20. On October 15, 2024, he was travelling from Dombivali to his ITI college in Mulund, when he fell off the overcrowded coach

"I let three trains go, hoping for one with less rush... As I tried to board, someone pushed and I fell"

Monica More, 27, bank employee. On January 11, 2014, More was boarding a CSMT-bound train when she slipped into the gap between the train and platform at Ghatkopar

The way out?

In 1994, a report of the Standing Committee on Railways headed by CPI(M) leader Somnath Chatterjee, said, “The crowd (in the Mumbai locals) is so heavy that there are about 10 passengers to a square metre. The Committee recommended that top priority should be given to increase the lines/rakes in such crowded sections like Borivali-Virar section... More suburban trains should be introduced in such busy sections.”

More than 30 years later, Borivali-Virar continues to be among the most crowded and congested routes.

Over two decades after Chatterjee’s report, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India in 2016 and a Public Accounts Committee (PAC) report in 2017 made similar suggestions.

In its recommendations, CAG said that the carrying capacity of EMU rakes should be enhanced, the frequency of suburban train services should be increased, and effective action taken to operate train services as per the schedule. It also called for establishing a separate organisational set-up for the suburban train services to increase organisational efficiencies in target zones.

The committee directed the Railways to redesign the coaches on the lines of coaches with automatic doors similar to those used in Metro trains and increase the number of coaches to 15 in each train.

The broader infrastructural roadmap, they say, lies in the ongoing MUTP 3A, a Rs 33,690-crore project launched in 2019 to address congestion, safety, and service reliability. It includes major expansions such as the extension of the Harbour Line from Goregaon to Borivali, the addition of fifth and sixth tracks between Borivali and Virar, a fourth line between Kalyan and Asangaon, and third and fourth lines between Kalyan and Badlapur. These expansions aim to segregate suburban and long-distance services and improve frequency. But given the scale of the network and its operations, it’s an uphill task.

Some transport experts have also suggested hybrid trains with both AC and non-AC coaches – for example, a 15-coach train with nine non-AC and six AC coaches.

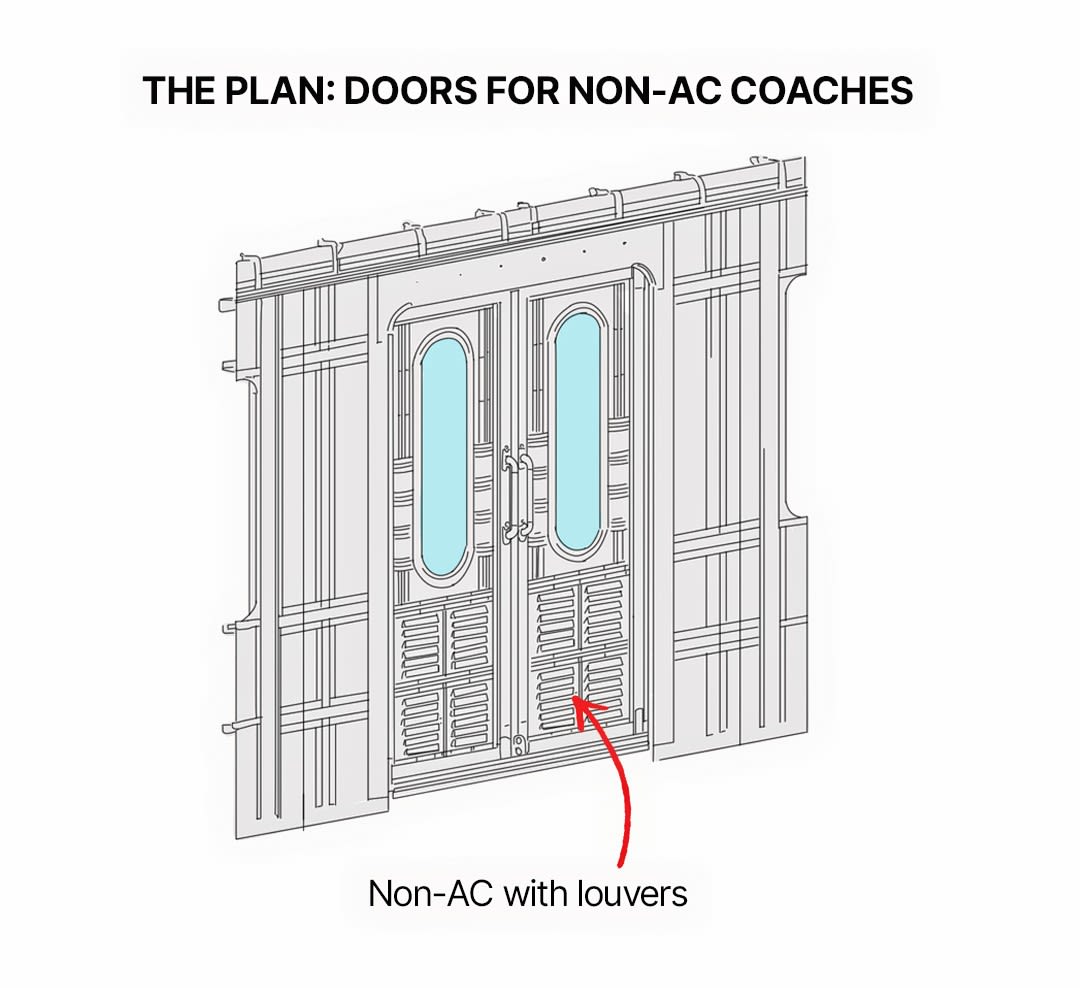

According to Swapnil Nila, Central Railway spokesperson, after the Mumbra accident, the Railway Minister held a review with officials of the Railway Board and the Integral Coach Factory (where the rakes are built) to explore the possibility of automatic door systems for non-AC trains.

“A key concern was ventilation, since non-AC coaches rely on open doors for airflow. It was decided that new non-AC trains will feature louvered doors, roof-mounted ventilation units, and inter-coach vestibules to address both safety and airflow. The redesign tackles overcrowding and ventilation without compromising on commuter safety,” says Nila.

The new safety measures include a plan to install louvered doors in non-AC trains

The new safety measures include a plan to install louvered doors in non-AC trains

These upgraded trains are expected to be introduced by January 2026, but their success can only be determined after the implementation.

The proposed MUTP 4, now under consideration, aims to build on the reforms outlined in earlier phases. It includes further track expansions and signalling upgrades. A key focus of this phase is improving access and safety on footpaths, skywalks, and pedestrian crossings. The larger vision of the project is to achieve “Zero Deaths” across Mumbai’s suburban railway network.

“We are thinking of 20 years from now on how travel demand will evolve, while also working on identifying new routes and easing pressure on the existing ones. One of the key areas we’re studying under the new MUTP is whether Central and Western Railway systems can be made interoperable, so passengers get smoother east-west access across the Mumbai region,” said an official of the Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation who is involved in the planning.

With Dheeraj Mishra, New Delhi; Illustrations: Komal