Andamanese Hindi,

Arabic-Malayalam, & Hinglish

The colourful and chaotic world

of languages in India

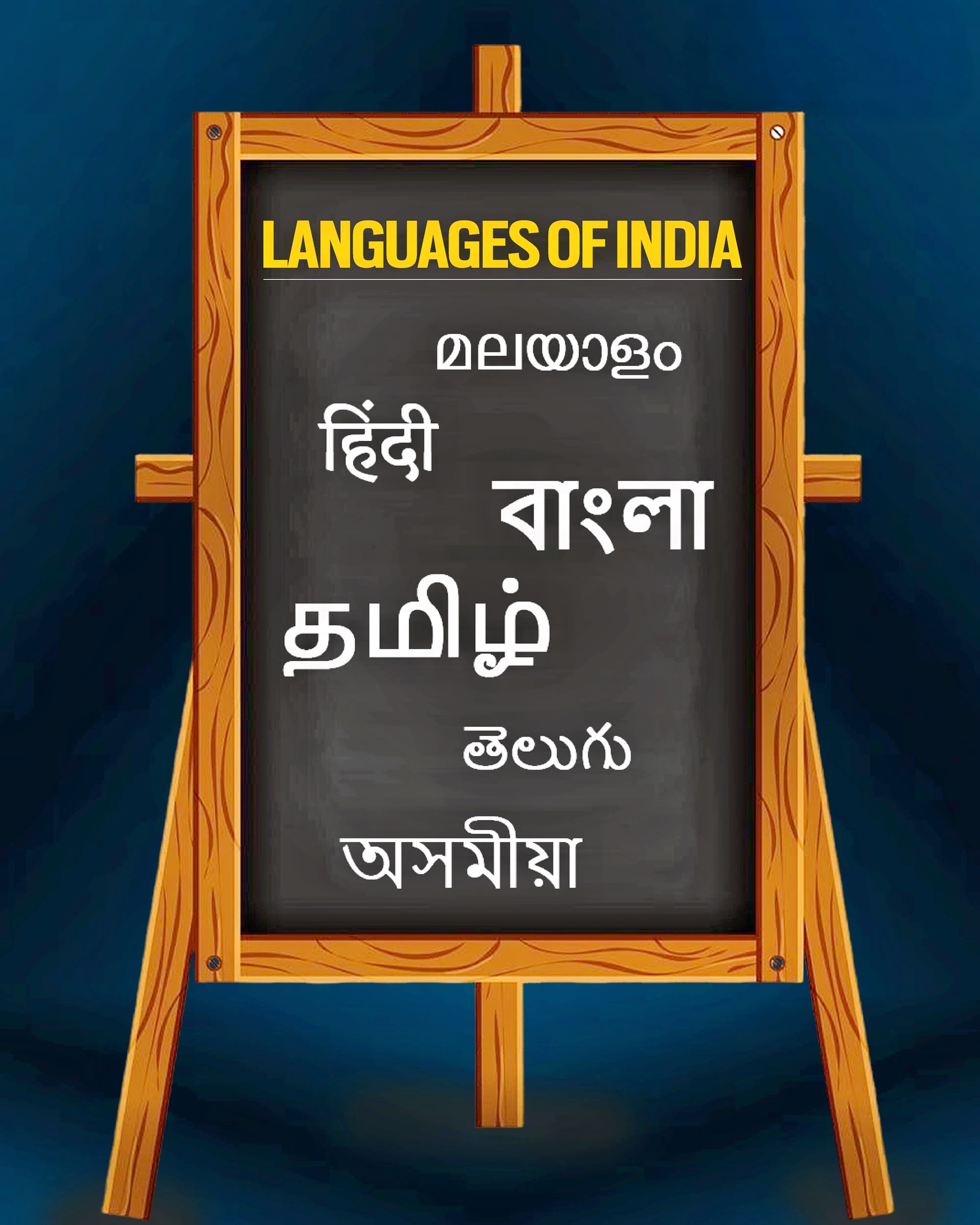

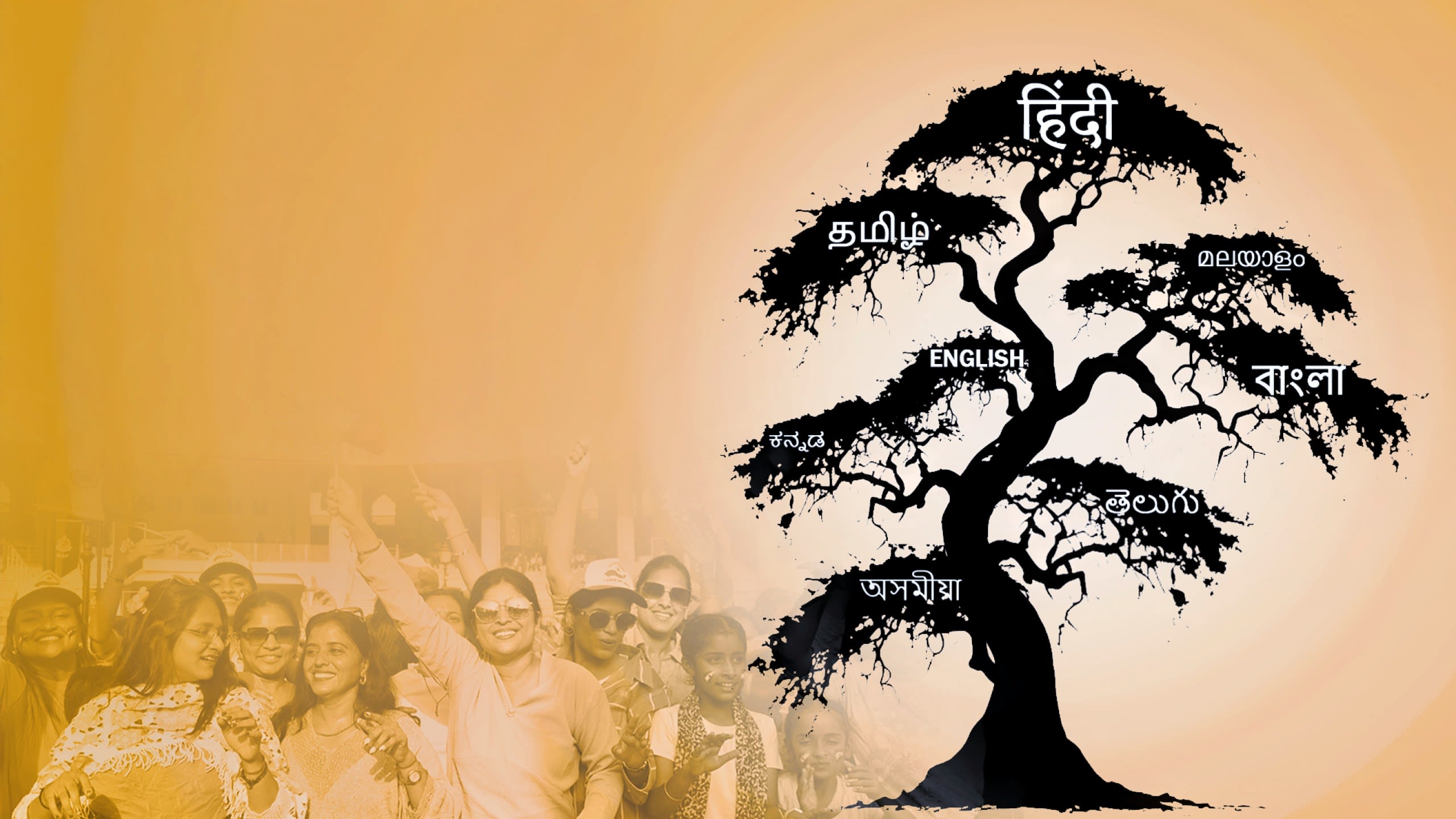

India's multilingual landscape reached its present form after millennia of migrations and mixing. It has been in many ways its greatest source of strength, and yet at times the cause behind some bitter political skirmishes. In this Indian Express Research series 'Languages of India', we look at this linguistic landscape through stories that trace its many tongues.

From the first Linguistic Survey of India to the fading voice of Awadhi in Lucknow, and from the forgotten worlds of Arabic-Malayalam and Arabic-Tamil to the efforts to keep some dialects alive, the series offers a deep understanding of what it means to speak, write, and live in many languages. And what is lost, or gained, when a language fades into silence.

AWADHI:

A language from

the Oudh struggling to retain its roots

Nikita Mohta

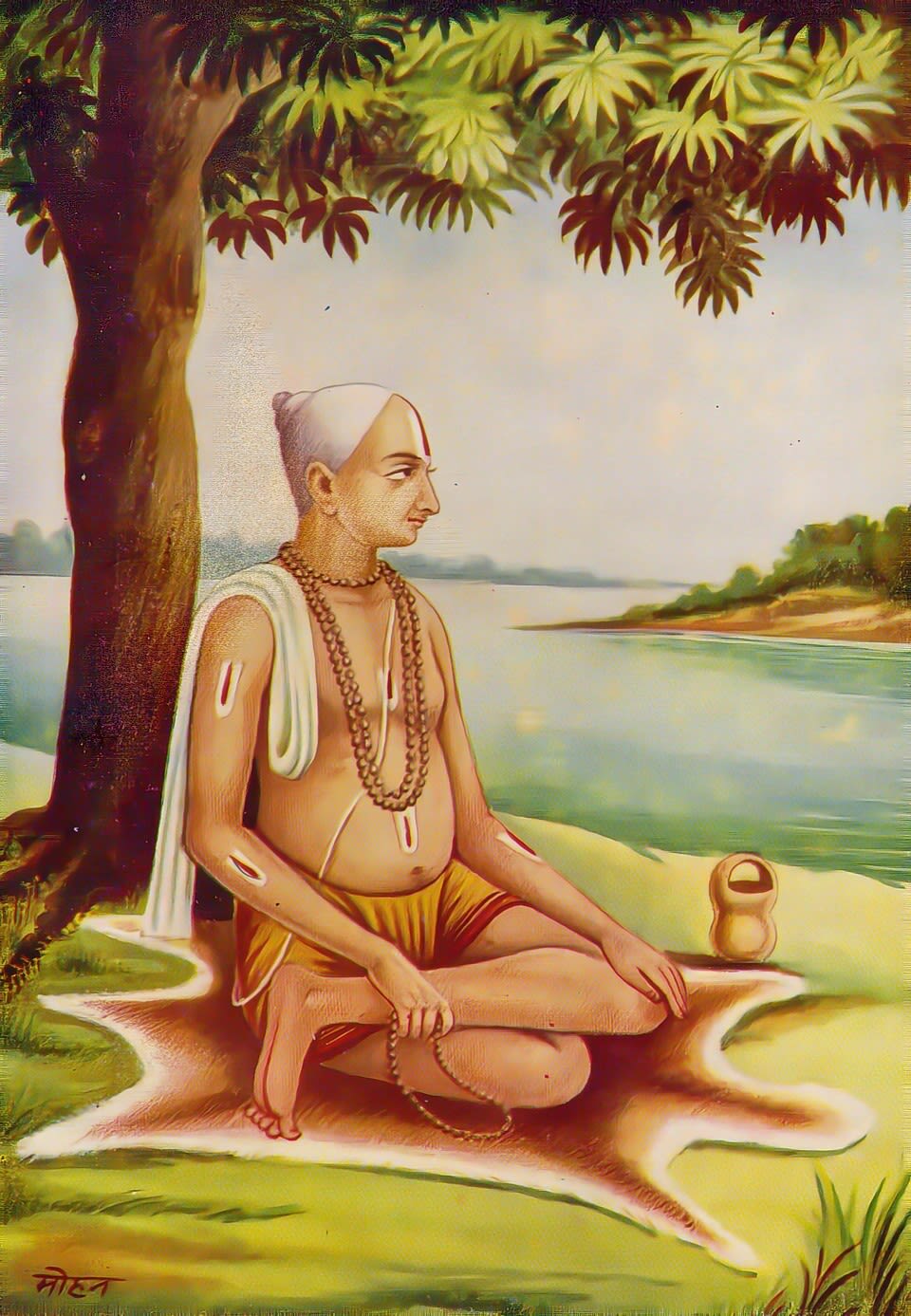

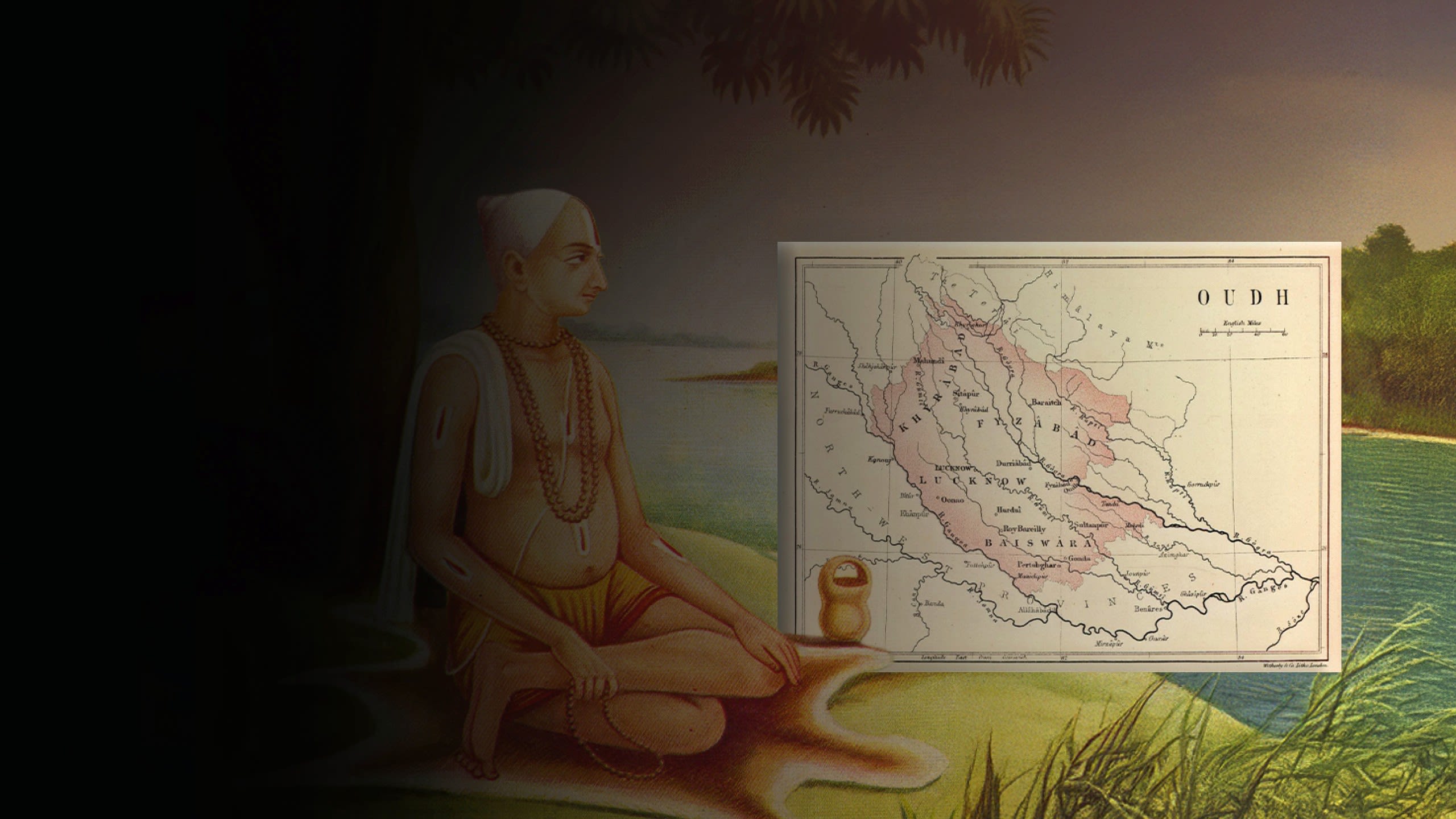

Awadhi, established as a literary language in the 14th century and widely spoken in Uttar Pradesh and surrounding regions, now finds itself overshadowed by Hindi and is often relegated to the status of a dialect

Anne Murphy, Professor at the University of British Columbia in Canada, argues that Awadhi was established as a literary language in North India in the 14th century, while Braj followed in the early 15th century.

“Labeling Awadhi a ‘dialect,’ is a political act — a fabrication.”- Anne Murphy

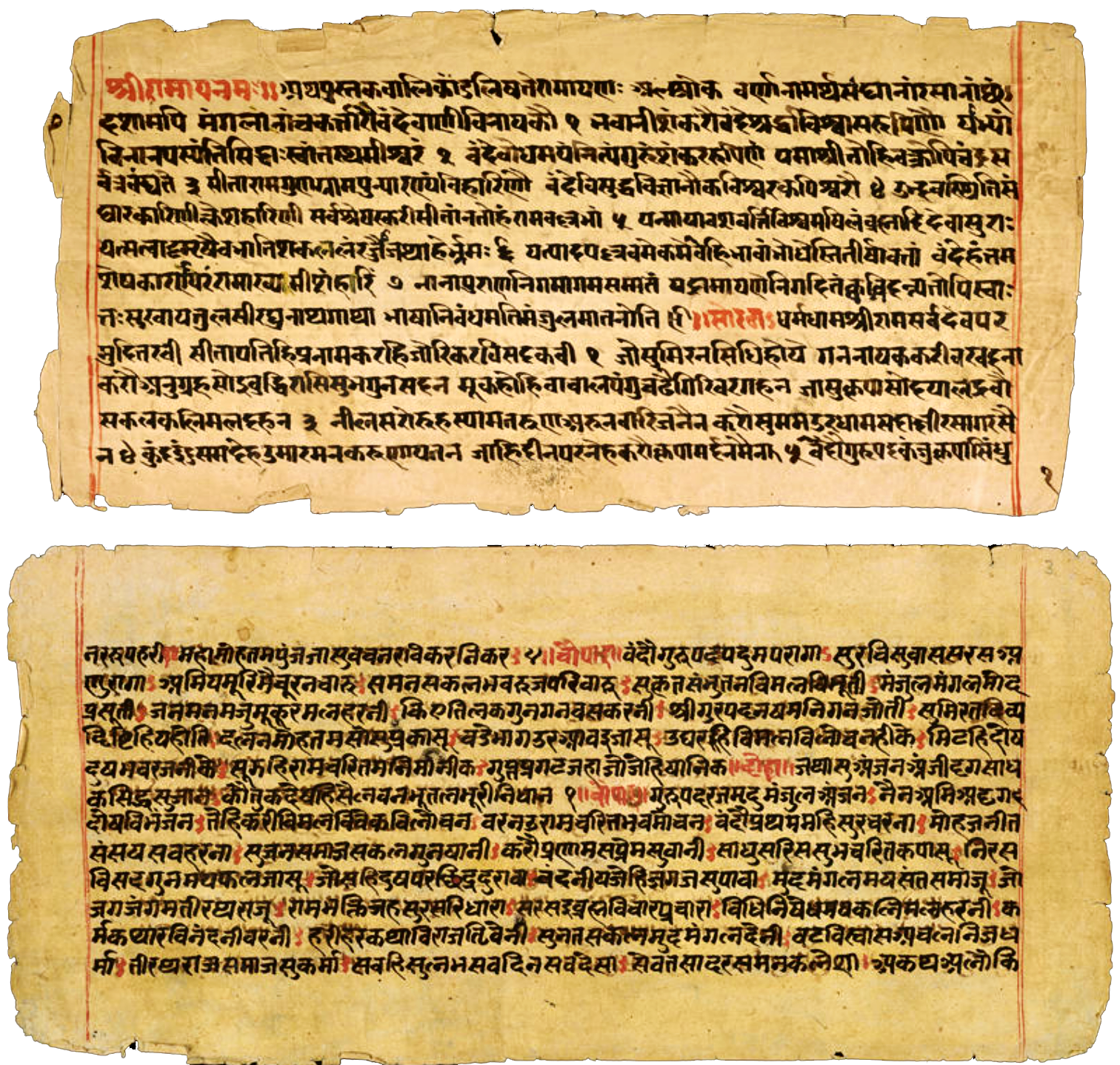

Picture of author, Tulsidas published in the Ramcharitmanas, 1949 (Wikimedia Commons)

According to journalist and author Madhuker Upadhyay, the 1857 revolt in Lucknow turned the British against the region, leading them to target and persecute the Awadhi-speaking population.

Poonam Shukla, an Awadhi-speaking resident of Nepal, says “If Hindi had been the language of the masses at the time, Tulsidas’s Ramayan would have been written in Hindi, not Awadhi.”

A 19th century manuscript of the Ramcharitmanas (Wikipedia)

The (consciously) forgotten worlds of Arabic-Malayalam and Arabic-Tamil

Adrija Roychowdhury

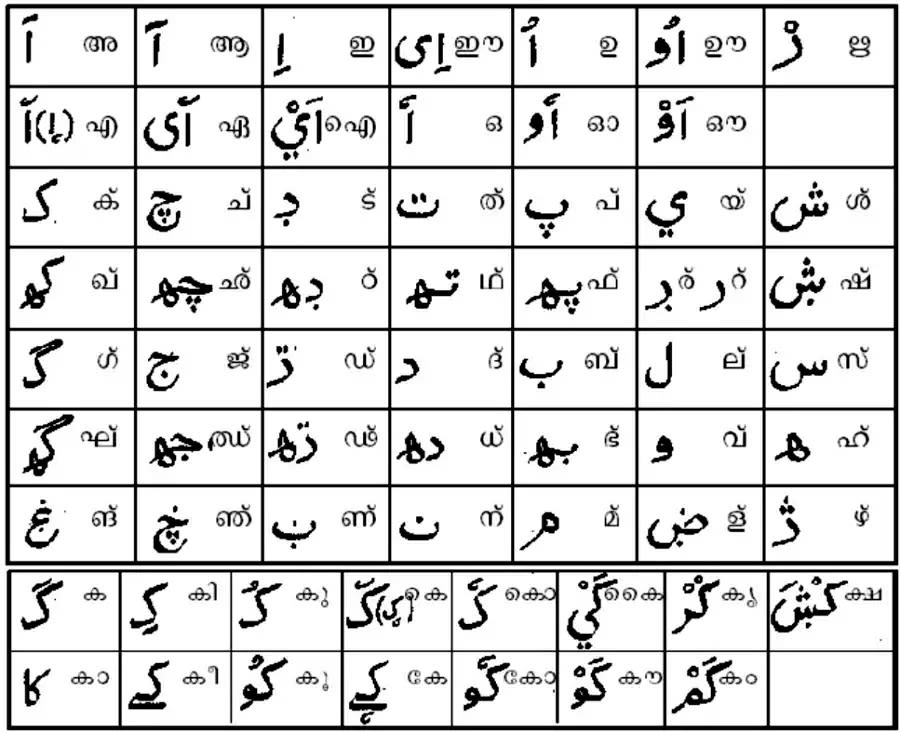

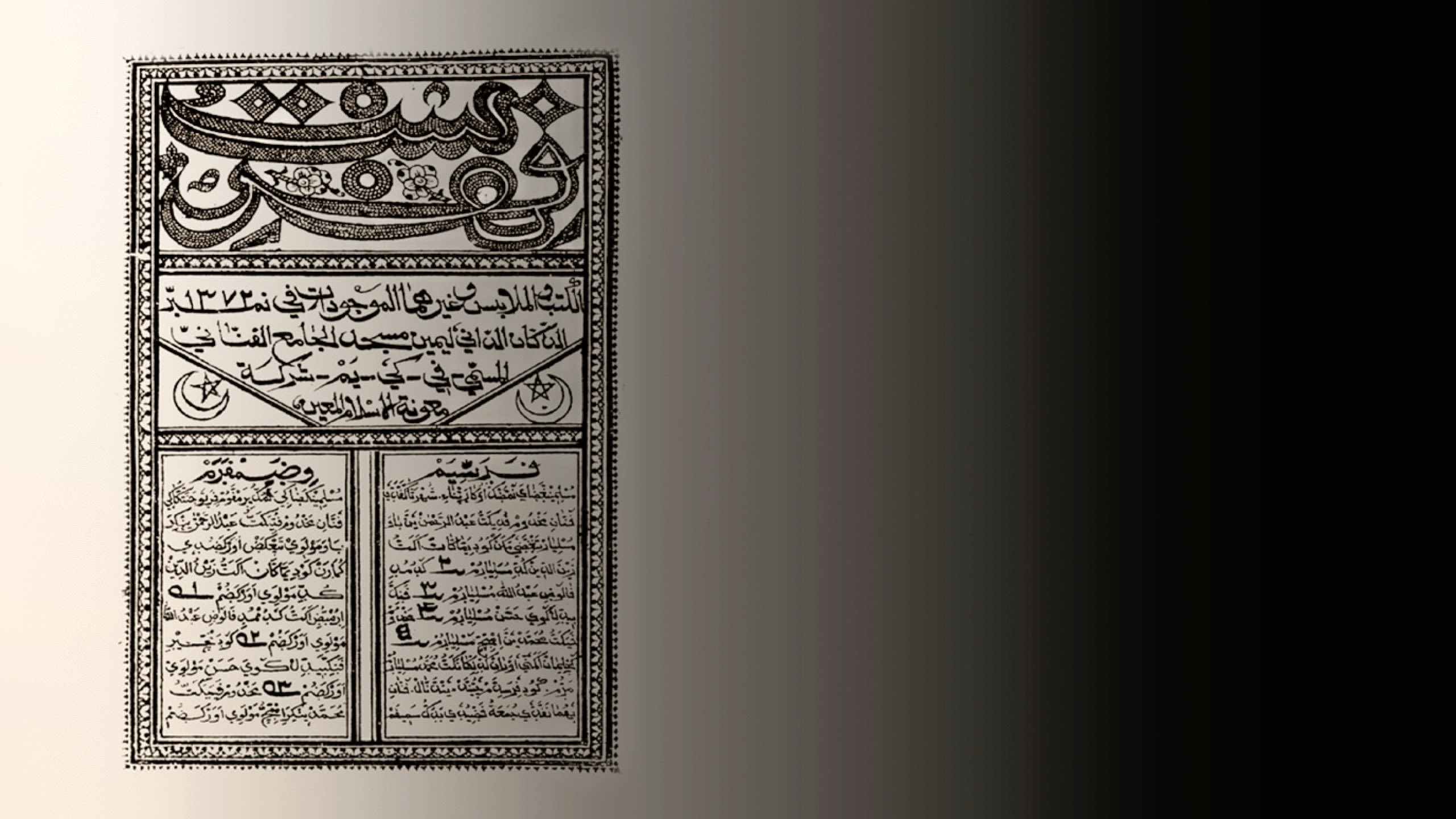

The Arabic script influenced languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, and Malayalam. While most of these traditions lay forgotten, there have been fresh efforts in the recent past to explore and preserve two particularly major language systems — Arabic Tamil and Arabic Malayalam.

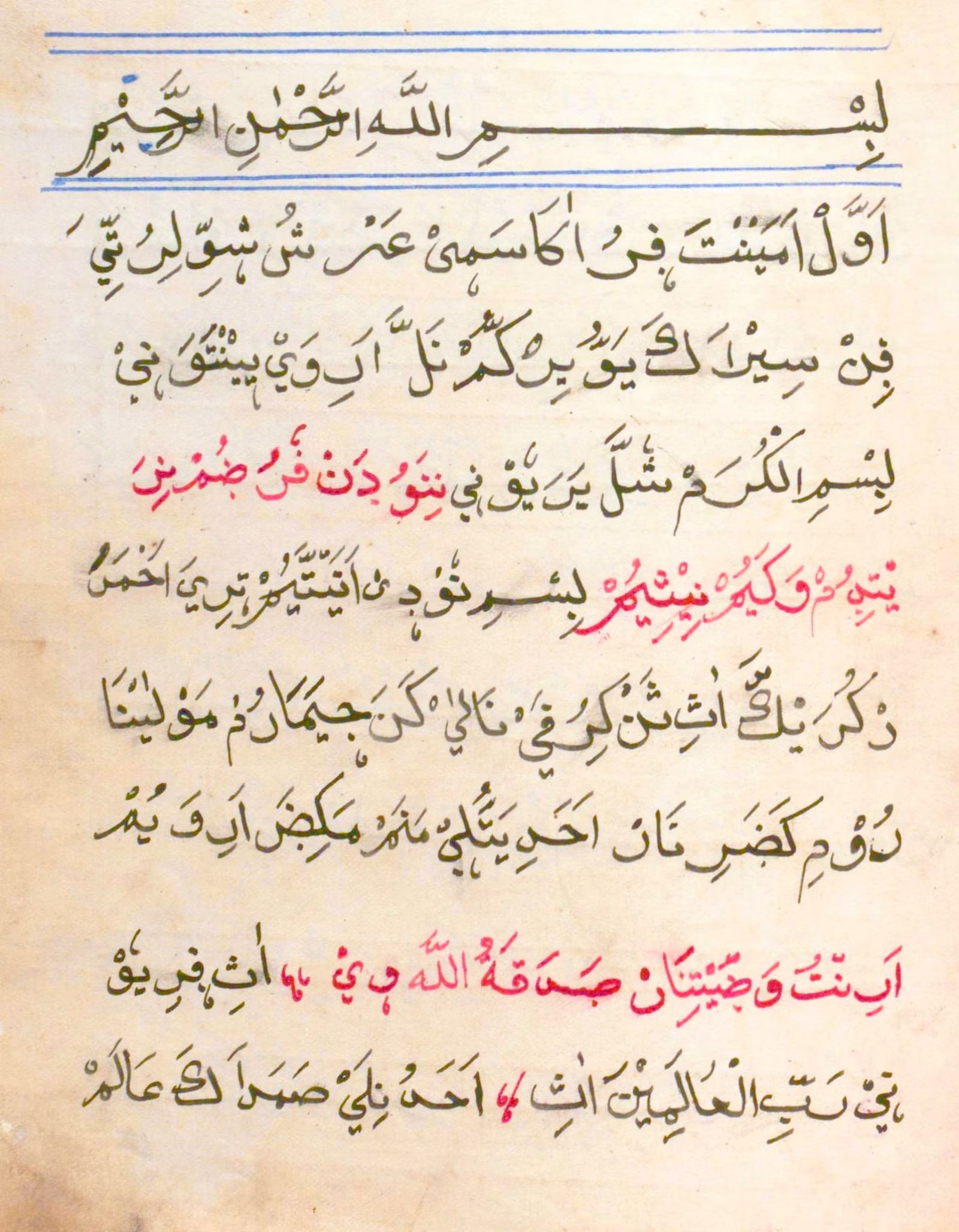

A seventeenth-century Sufi poem Bismil Kuram by Thuckalay Peer Mohammed Appa in Arabic-Tamil script from a 20th century manuscript. (Reproduced with permission from Torsten Tschacher)

Historian Torsten Tschacher explained that trade was the most important factor in the proliferation of the Arabic script. There was a practicality involved in knowing the Arabic script, much the same way in which the Roman script came to be used later.

“The major empires like the Ottomans, Saffavids, the Mughals as well as the British, definitely played a role in popularising both the Indian Ocean trade as well as the Arabic language and script,” says Professor Mahmood Kooria.

The Arabic-Malayalam alphabet (Wikimedia Commons)

The Arabic script underwent a sharp decline from the early 20th century with the emergence of social reform movements in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The famous Malayalam writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, identified Arabic-Malayalam as the ‘historical blunder’ of the Muslim community in the region.

The standardisation of Urdu in the early 20th century as the dominant Islamic school curriculum was yet another reason for the decline of the Arabic script.

The colourful and chaotic

world of 'Languages in India'

Vanishing

voices of the mountains: The struggle to preserve Pahari languages

Aishwarya Khosla

Spoken by millions in the regions of the Western Himalayas, Pahari languages remain unrecognised in India’s official language policies.

While these languages and dialects, even those in geographic proximity, phonetically differ from each other, linguists have traditionally lumped these vernaculars under the catch-all ‘Pahari’.

Photo courtesy: Abhishek Mitra

Western Pahari, spoken primarily in Himachal Pradesh and parts of Jammu, includes languages such as Kangri, Mandeali, Chambeali, Gaddi, and Bhalesi.

Central Pahari covers Garhwali and Kumaoni, the principal languages of Uttarakhand. Eastern Pahari is represented almost entirely by Nepali, once known as Khas Kura or Gorkhali.

They are united by their mountain origins and the cultural traditions they carry: folk tales, devotional songs, and seasonal idioms.

Photo courtesy: Abhishek Mitra

Despite decades of advocacy, the Pahari languages have yet to gain recognition under the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

The emergence

of Hinglish in advertising, Bollywood,

and everyday

life in India

Mira Patel

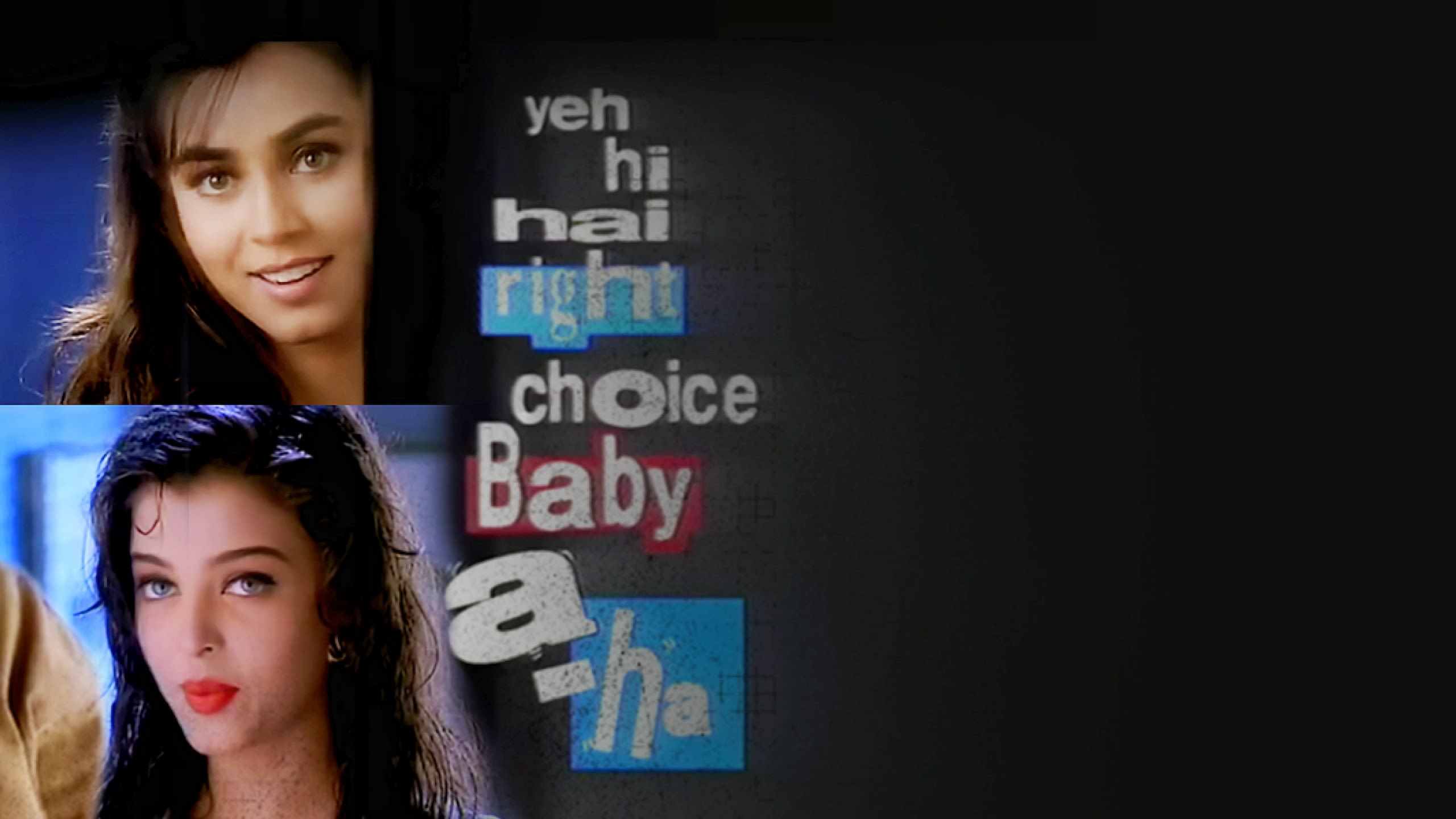

In the 1980s, an advertisement for Vicco Turmeric changed the way India spoke about beauty. The catchy melody, “Vicco Turmeric, nahi cosmetic,” marked a shift in the way brands spoke to Indians.

A marriage of Hindi and English — Hinglish — was born. It grew to mark the shifting identity of a nation in motion.

This hybridisation has influenced the lexicons and structures of both the Indian and English languages. Many English words, such as chutney, khaki, and mantra, have origins in Hindi or Urdu, while Hindi has adopted English words like botal (bottle), kaptaan (captain), and tamatar (tomato).

The advent of Hinglish advertising began in earnest with Pepsi in 1990. The tagline “Yehi hai right choice, baby, aha!” signalled to Indian youth that Pepsi, not Thums Up, was the global choice with an Indian flavour.

“The ads influence the culture, and the culture influences the ads.”- Falguni Vasadeva, Professor at MICA and influencer.

ANDAMANESE

HINDI:

how Andaman and Nicobar Islands came

to embrace a unique linguistic identity and take pride in it

Adrija Roychowdhury

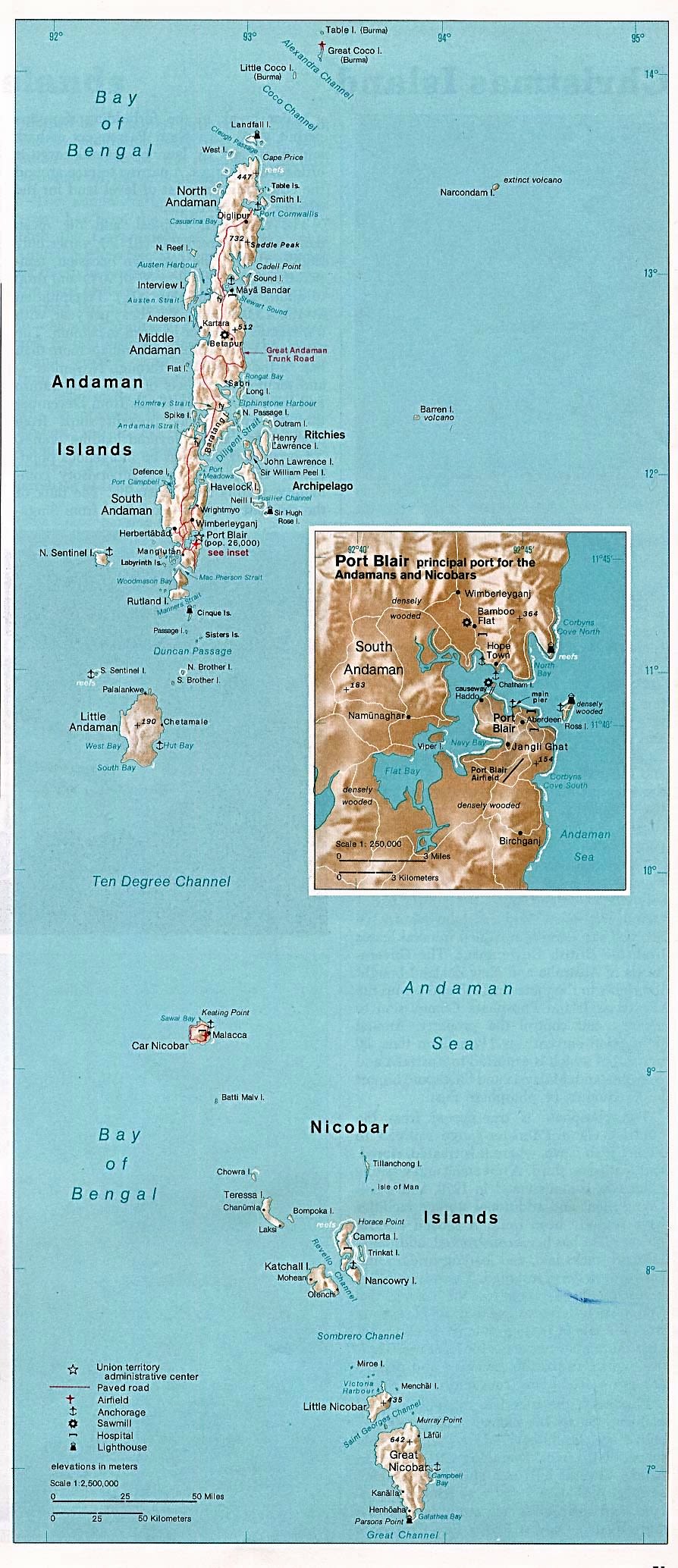

For 26-year-old Lephay, her mother tongue is mostly an idea lost in time, one that was spoken long ago by her grandparents. The Great Andamanese is a near-extinct language, with less than 10 speakers alive today.

The tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Wikimedia Commons)

As the native language vanishes swiftly, what has come to take its place is Hindi, which has connected the tribal and non-tribal inhabitants of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The proliferation of Hindi in Andaman and Nicobar, say scholars, is a product of the long history of migration and settlement of multiple Indian communities in the islands. “One can say that the Andaman language landscape reflects the history of South Asia,” says linguist Ganesh Devy.

Map of Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Wikimedia Commons)

“Hindi is our national language. They speak very proudly. The kind of love for Hindi I see in Andaman is something I didn't even see in the Hindi heartland.”- linguist Anvita Abbi

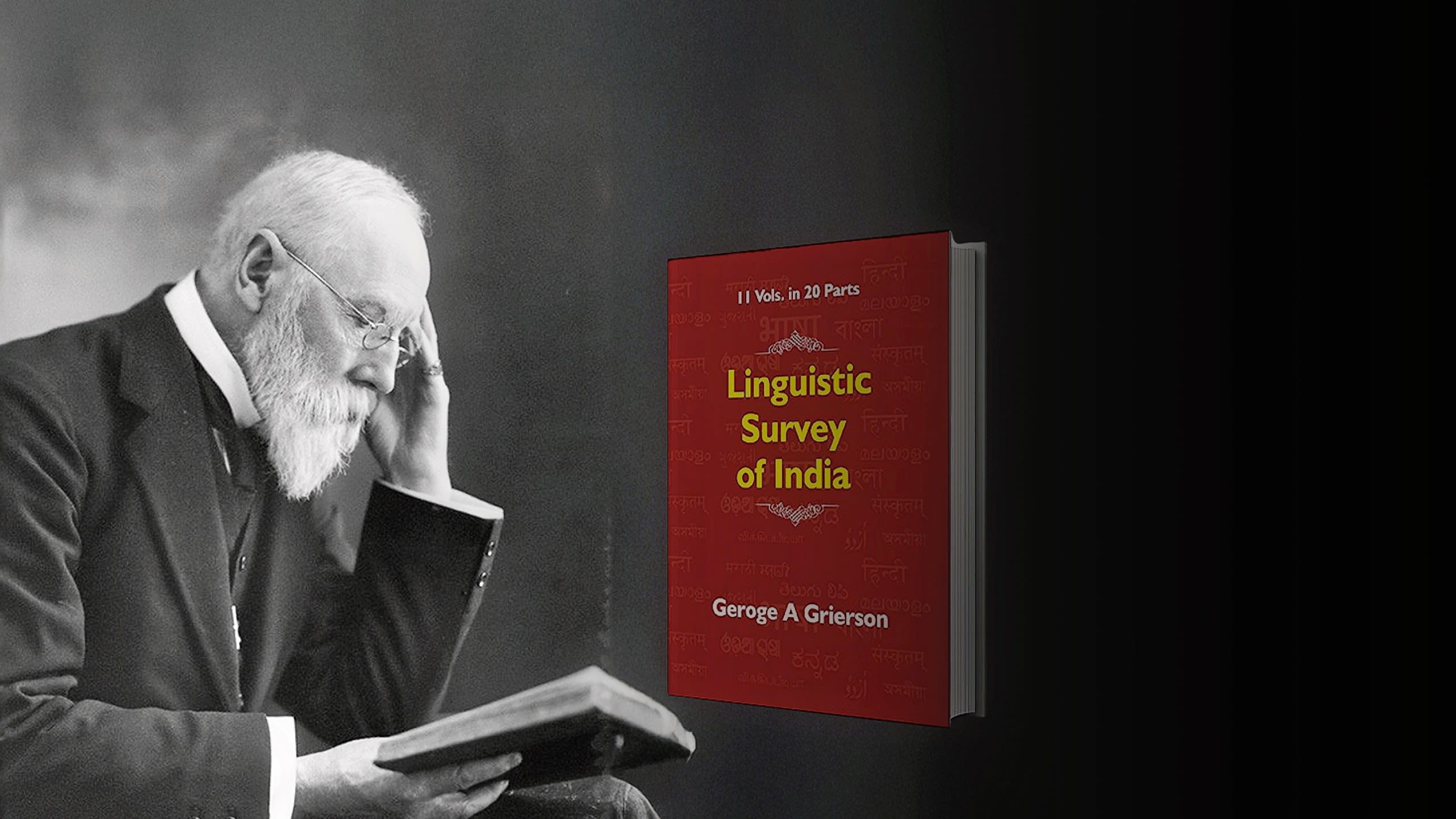

What George Grierson’s First Linguistic Survey of India tells us about multilingual South Asia

Nikita Mohta

George Grierson’s First Linguistic Survey of India identified over 700 linguistic varieties across South Asia by 1927

Irish-born Indian Civil Services officer George Abraham Grierson’s monumental project spanned over three decades (1901-1928).

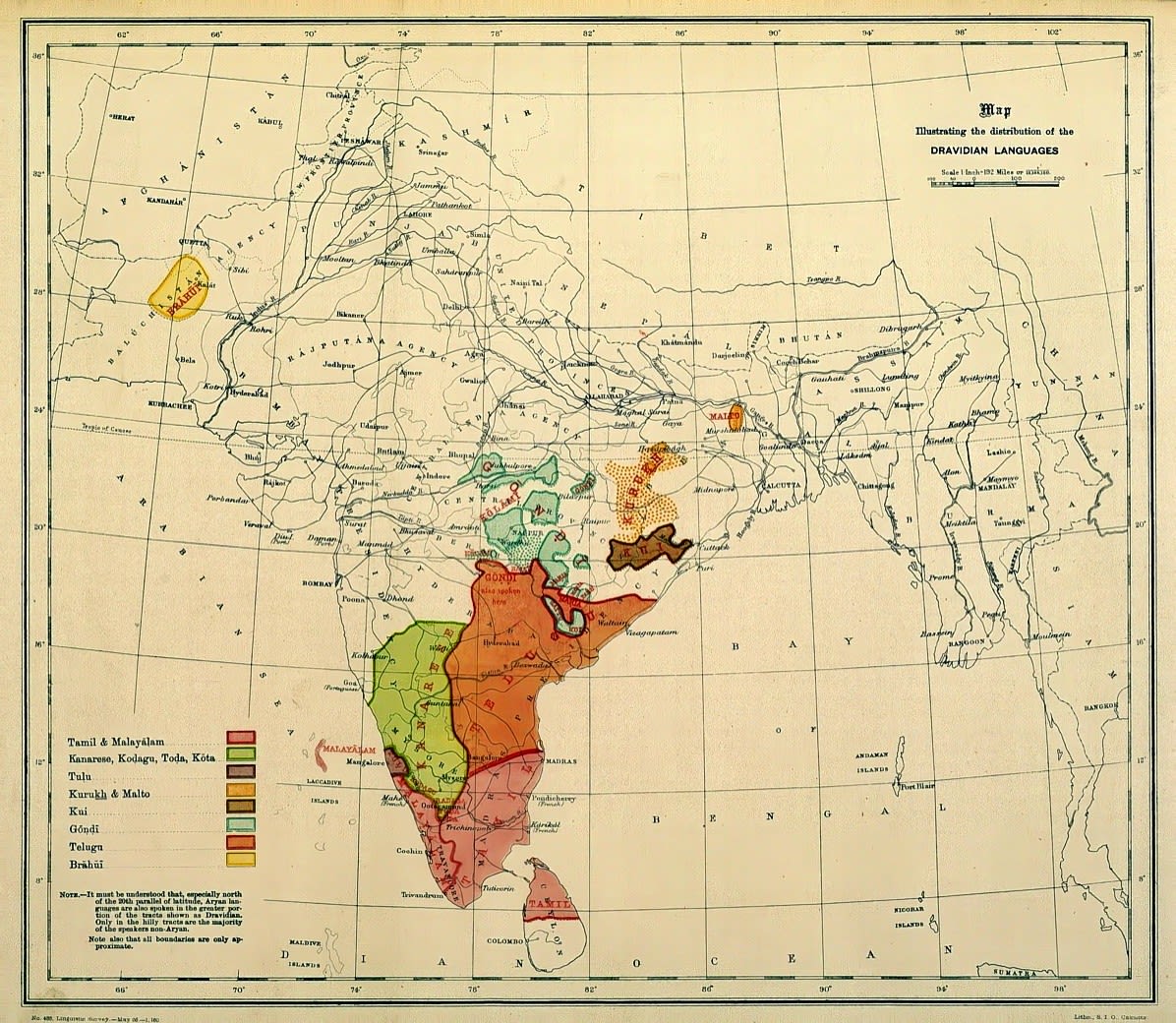

The Survey documents more than 700 linguistic varieties across South Asia, offering detailed lexical and grammatical data for 268 varieties within the four major South Asian language families. It remains a foundational reference for any discussion on India’s linguistic landscape.

“If there’s any inheritance from the colonial enterprise, it’s the desire for one language, one community. And somehow, our politics seems to operate within that framework,” says linguist Ayesha Kidwai

A map marking Dravidian Languages from the LSI (Source: Wikipedia)

'Languages in India'

The fight to keep Punjabi alive in Pakistan

Nikita Mohta

Despite being the most spoken language in Pakistan, Punjabi lacks official status, while Urdu and English dominate the legal system, mass media and educational sectors of the country

“My grandparents and uncle would often warn me that Punjabi had too many swear words; it wasn’t a language for the educated,” says Syed Qasim Omer from Kotla Arab Ali Khan, a town in Pakistan’s Punjab province.

The roots of this linguistic marginalisation can be traced back to colonial Punjab, but became more apparent after the 1947 Partition. India embraced Sanskritised Hindi, while Pakistan adopted Urdu.

“Punjab became part of Pakistan because it was a Muslim-majority province under British rule.. And yet today, the majority language of that region [Punjabi] is denied to its own children.”- Anne Murphy, Professor at the University of British Columbia.

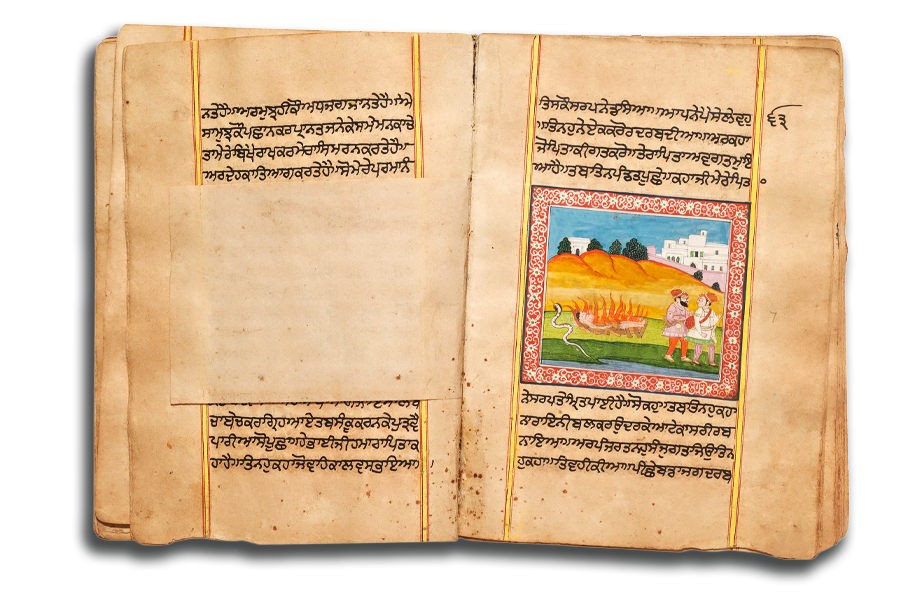

A Hindu illustrated manuscript written in the Gurmukhi script (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

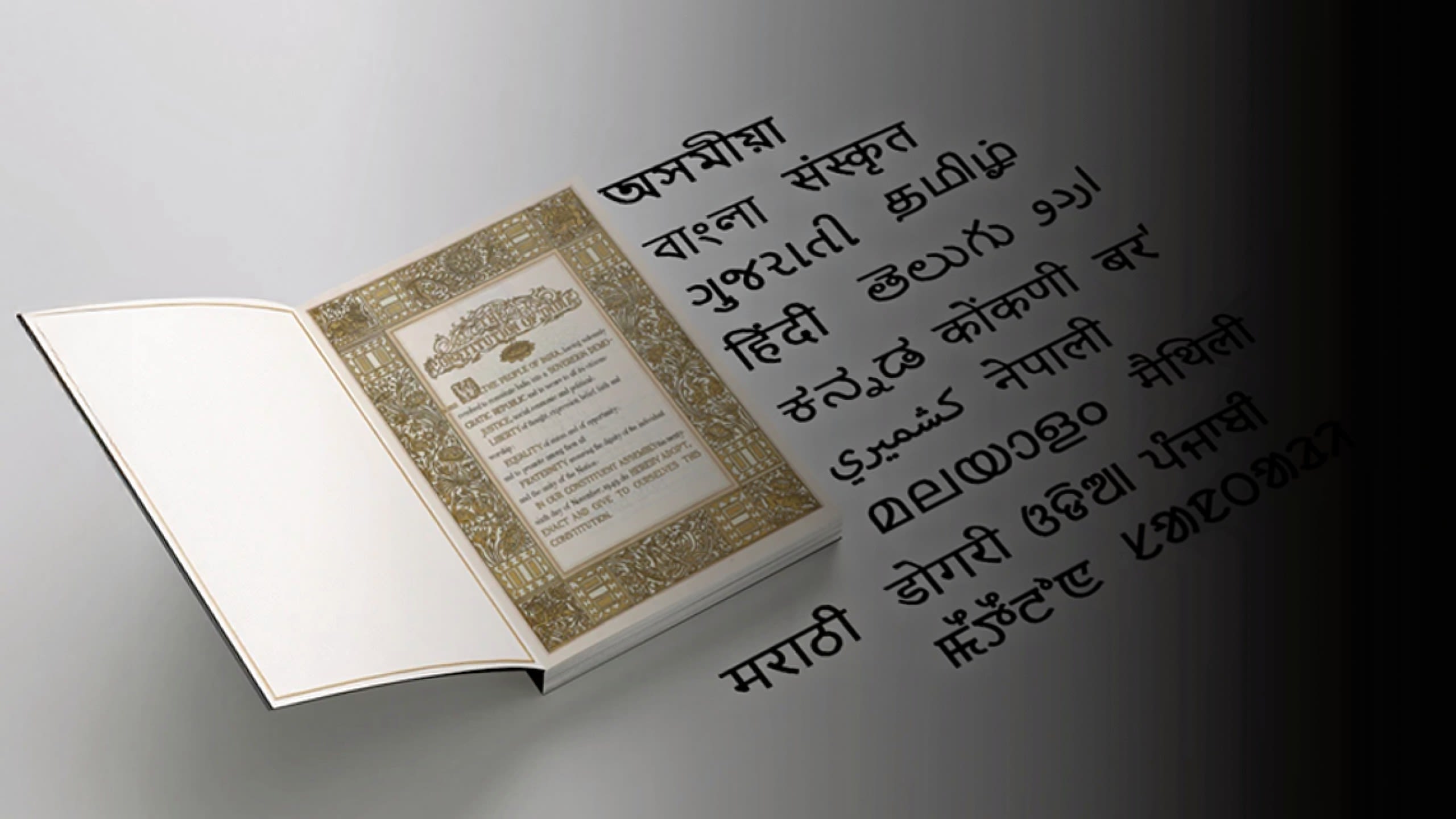

The Eighth Schedule of

the Indian Constitution: how language inclusion creates exclusion

Nikita Mohta

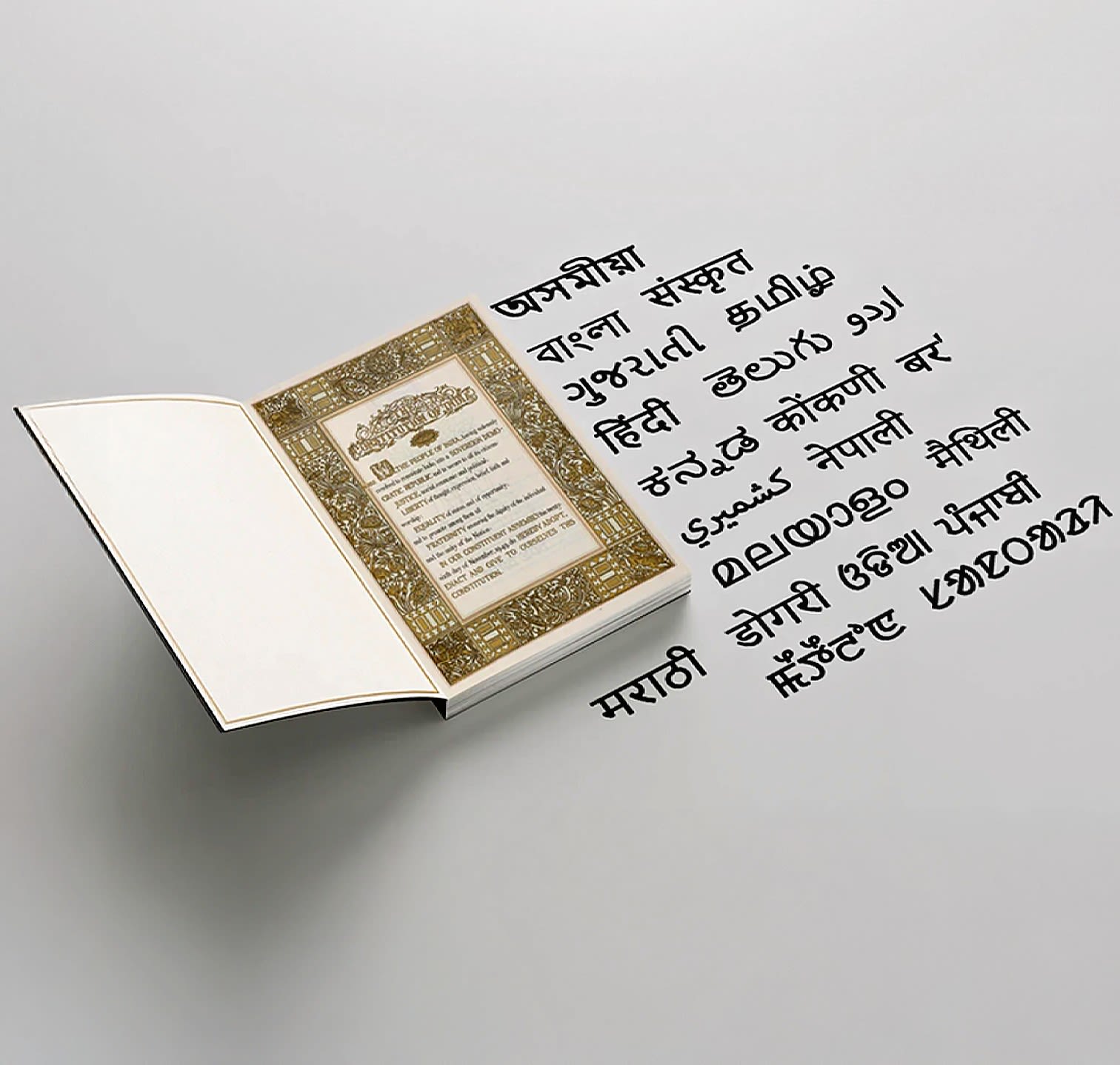

Linguists argue that the 22 languages currently on the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution “have gained power, recognition and prestige”, while others have been left to languish as ‘dialects’ or ‘minor languages’.

Initially, the Eighth Schedule included 14 languages: Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya (renamed to Odia in 2011), Punjabi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu.

Interestingly, English — despite its widespread use and role in official spheres — has never been part of the Eighth Schedule. A proposal for its inclusion was made in 1959, but it was firmly opposed by Jawaharlal Nehru.

Linguists R S Gupta and Anvita Abbi argue that the 22 languages currently on the Schedule “have gained power, recognition and prestige, while others have been left to languish under the yoke of such ‘demeaning’ labels as ‘dialects,’ ‘minor languages,’ and ‘tribal language.’”

Yet, Ananya Birla, who teaches at the National Law School of India University, argues that even

languages included in the Eighth Schedule, such as Manipuri and Bodo, and others recognised by state governments are endangered.

From Ashokan edicts and Manusmriti to modern novels: deciphering the

art and politics

of translation

in multilingual South Asia

Nikita Mohta

Translation in a linguistically diverse landscape like South Asia has played a crucial role in shaping cultural identity and addressing power imbalances.

Linguists Rita Kothari and Krupa Shah note that “it is possible to say that South Asia as a whole is a region constituted through translation.”

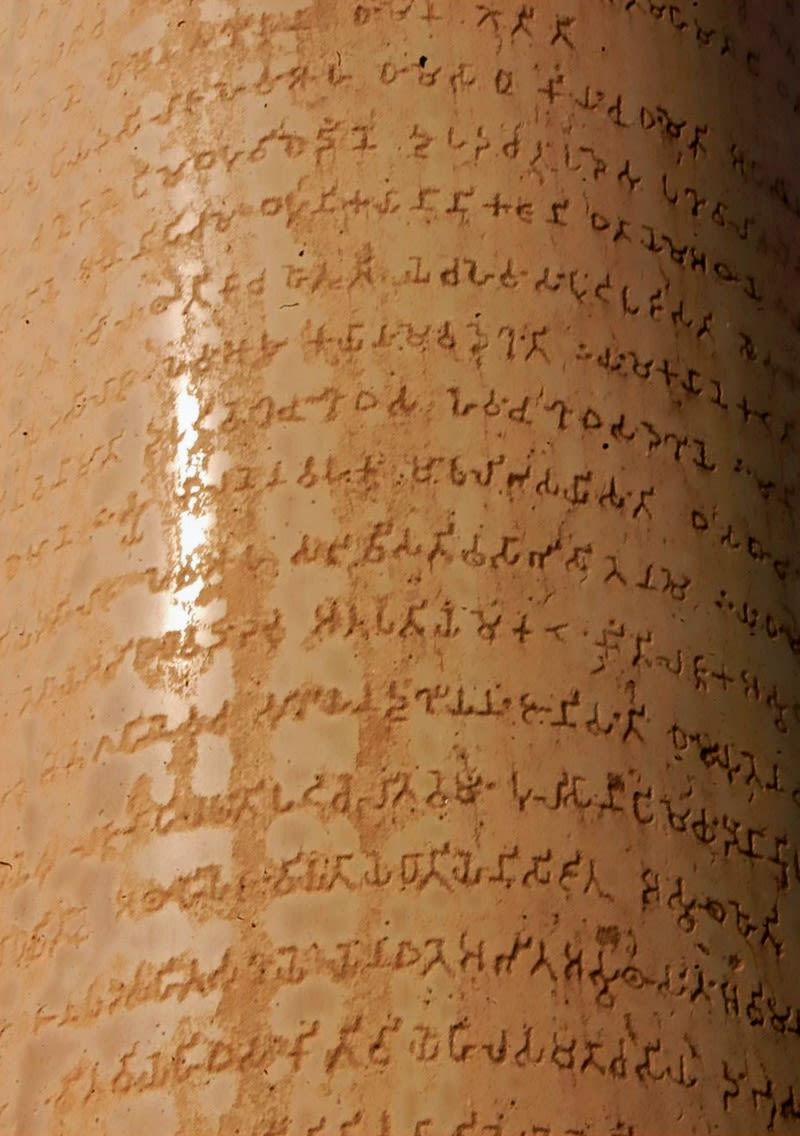

The edicts of Emperor Ashoka from the fourth century BCE, for instance, were multilingual—written in Sanskrit and various Middle-Indic dialects, often referred to as Prakrits.

India’s epics, in particular, have been translated the most.

Cultural transmission across regional languages, however, remains uneven. Kothari identified three key challenges: general apathy toward translation among writers, a shortage of multilingual translators, and the poor marketability of regional-language books—especially translations.

“A good translation can sometimes enhance the original text. That is why copyright often belongs not to the original author, but to the translator,” says Fuzail Asar Siddiqi, Professor at GITAM University, Visakhapatnam.

A Major Pillar Edict of Ashoka, in Lauriya Araraj, Bihar, India (Source: Wikipedia)

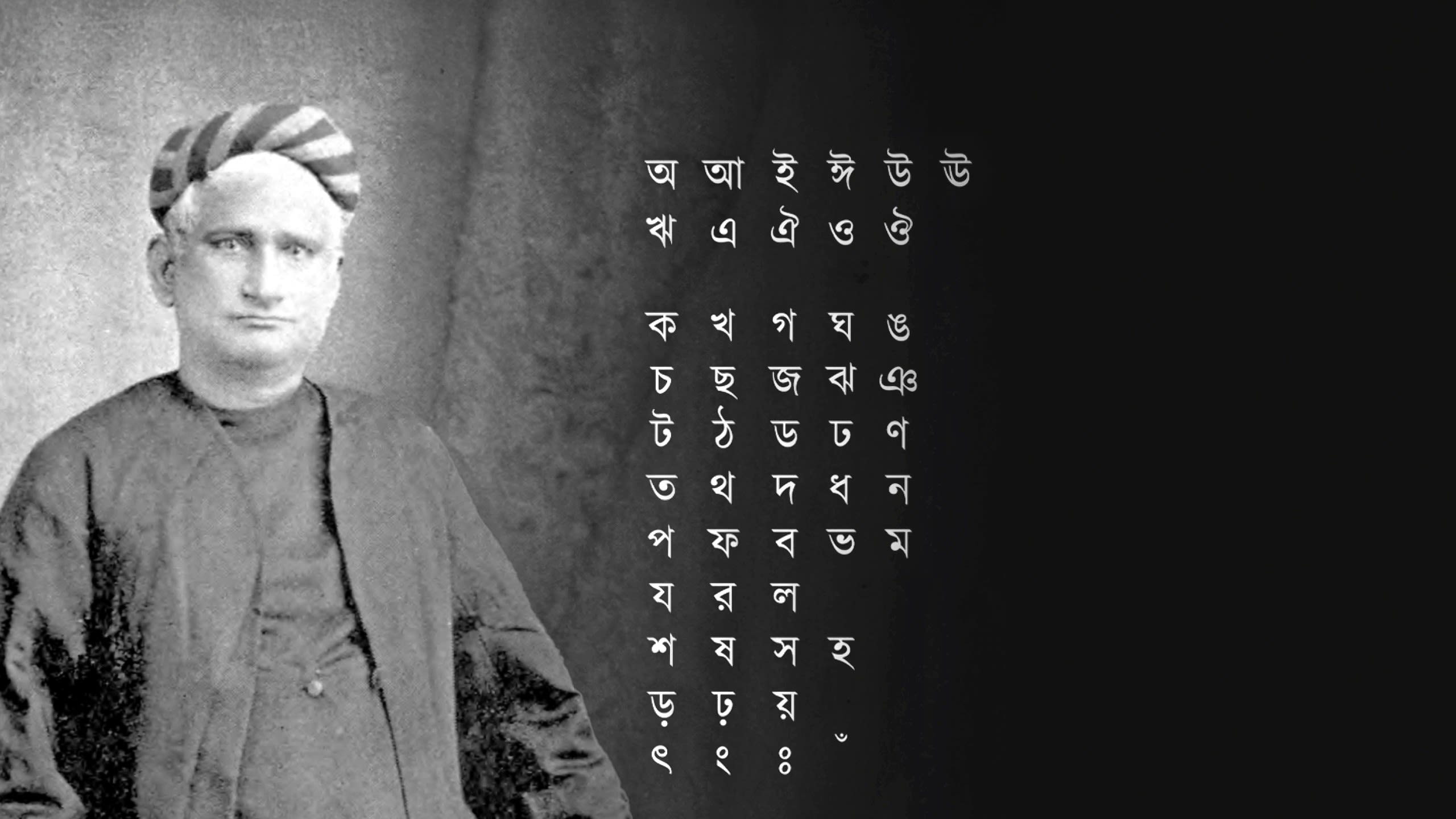

Bengali through the ages: from Islamic rule to the colonial era and beyond

Nikita Mohta

While Bengali is primarily derived from Magadhi Prakrit, over the years, the language has taken on new forms, ranging from the Sylheti dialect that absorbed Persian vocabulary to Radhi Bengali moulded by Vaishnava devotional poetry.

British colonialism in Bengal reshaped language and culture itself. What was once a rich tapestry of linguistic variety began to transform into a standardised form of Bengali.

The colonial linguistic engineering for instance produced Sadhu Bhasha—an artificially elevated literary form of Bengali. Characterised by elaborate compound verbs, rigid inflections and a heavily Sanskritised structure, Sadhu Bhasha became the language of courts, classrooms, and colonial bureaucracy.

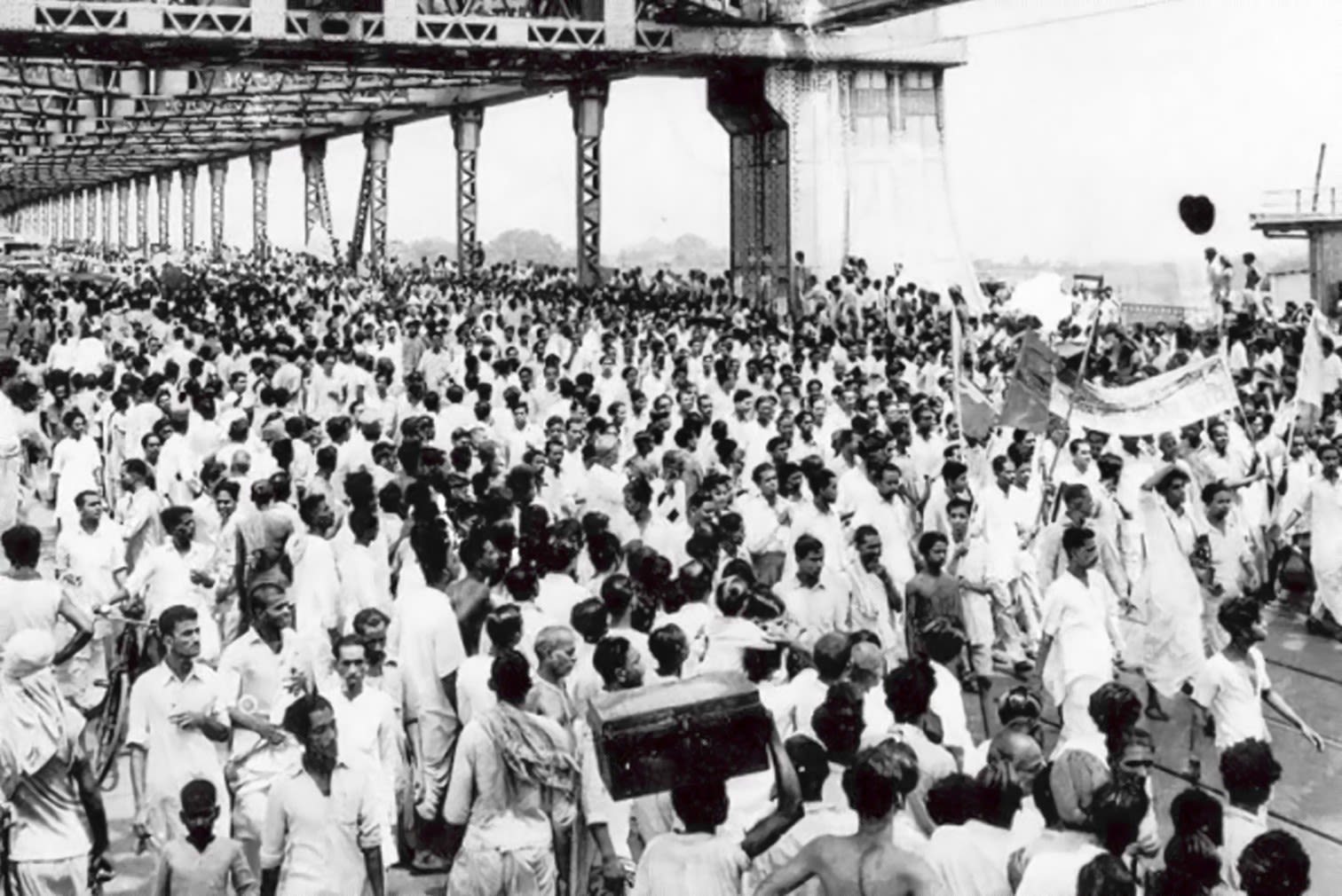

The Language Movement of 1952 in Dhaka, was about protecting the right to speak Bengali in all its diverse forms. Students from across regions marched in protest

By the late 20th century, West Bengal had largely adopted a standardised form of the Rarhi dialect, while other regional varieties became less prominent in public discourse.

The Language Movement of Bengal (Source: Wikipedia)