The Talented

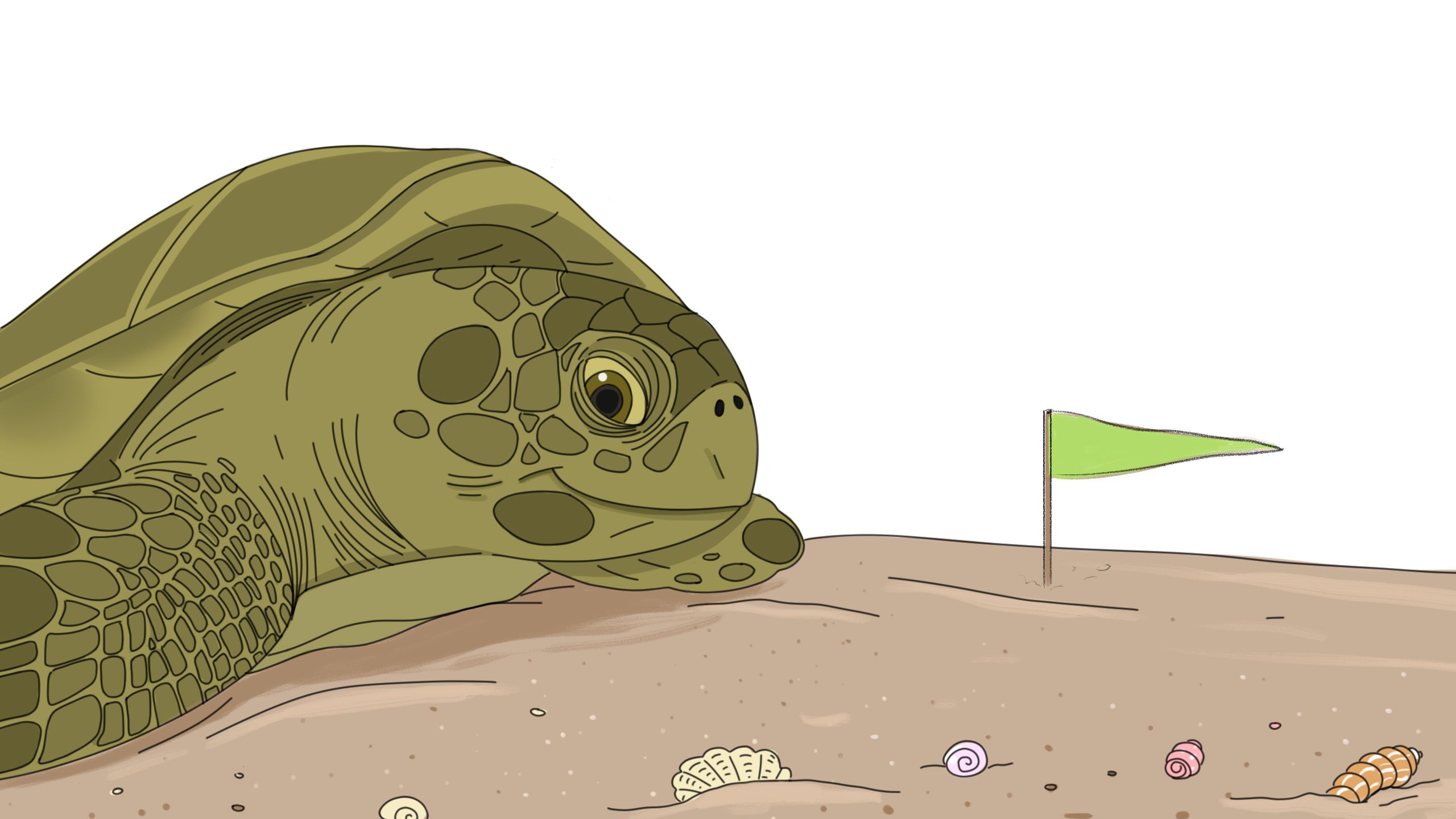

Mr Ridley

As it has always been for turtles, for the Olive Ridleys, life’s a race — for survival. How a unique conservation project in coastal Maharashtra is working to protect the turtles from natural predators and prying humans

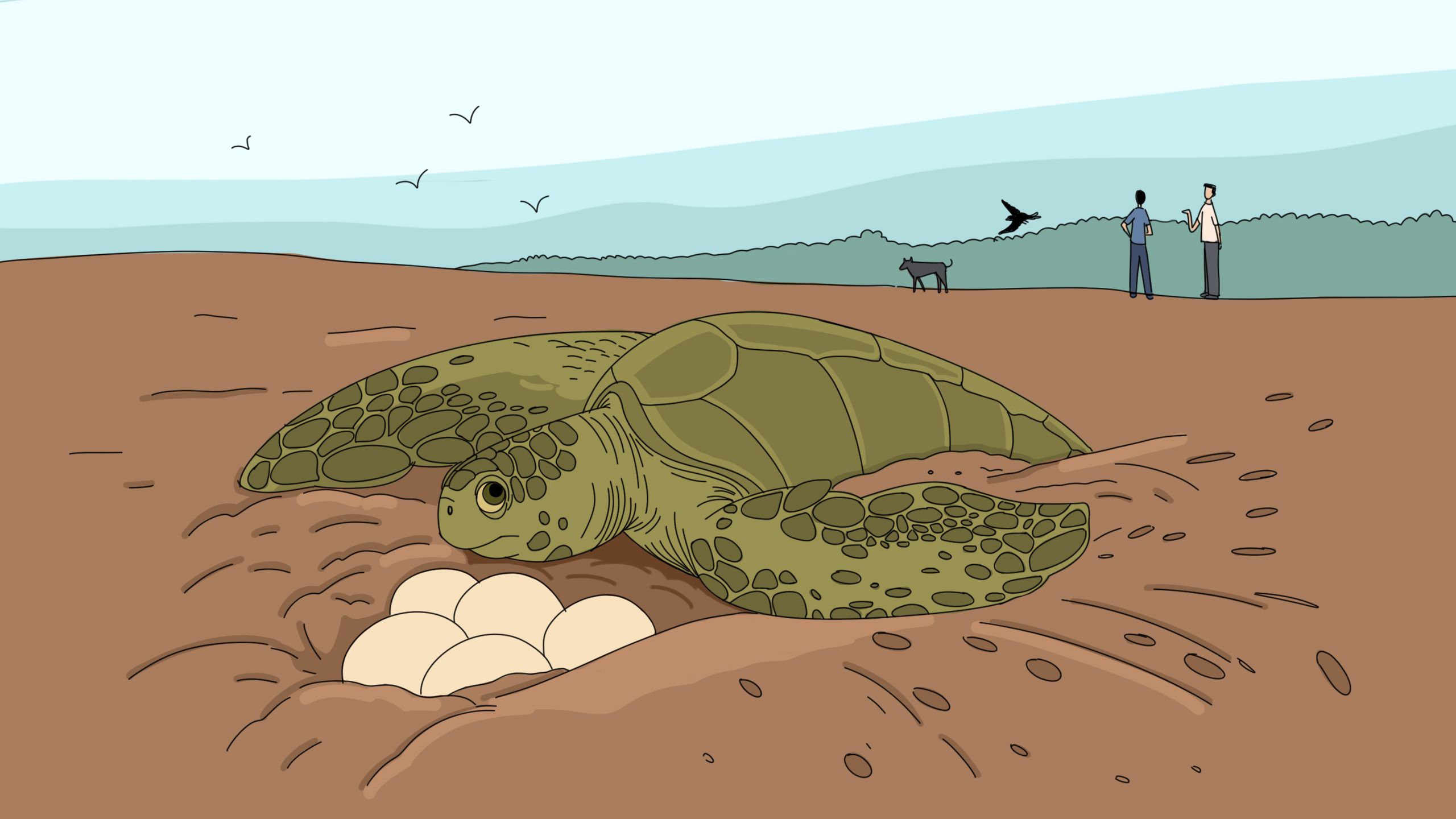

As the sun sets, the quiet nights along Guhagar beach in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri district are interrupted only by the crash of waves and the chirp of cicadas. On one such night in December last year, Akash Jangali and Vikrant Sangle’s patrol along the Bazaar Peth belt of the beach was interrupted by a noisy huddle of animals.

A flash of red light — considered “turtle-safe” — a wave of lathis and a jog down the shoreline confirmed their worst fears: a pack of dogs and golden jackals were burrowing their way into the sand to reach a nest of eggs recently laid by an Olive Ridley turtle. Shooing the predators away, the two men relocated nearly 80 eggs from the nest to a nearby hatchery.

A month later, on January 22 this year, another patrol team on the same stretch came across a female Olive Ridley nesting on the beach. The turtle had glistening metal tags, one on each of its front flippers, bearing the number ‘03233’.

The turtle’s discovery brought to the fore many revelations. In what became perhaps the first documented instance of a turtle travelling nearly 4,500 km from India's east coast to its west, Turtle 03233 — an inspection of her flipper tag revealed — had set off from the Odisha coastline in 2021, where it had been tagged by a team of Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) researchers.

Turtle 03233's migratory feat brings into focus the conservation efforts on India's west coast — until now, a lesser-known habitat of the Olive Ridleys.

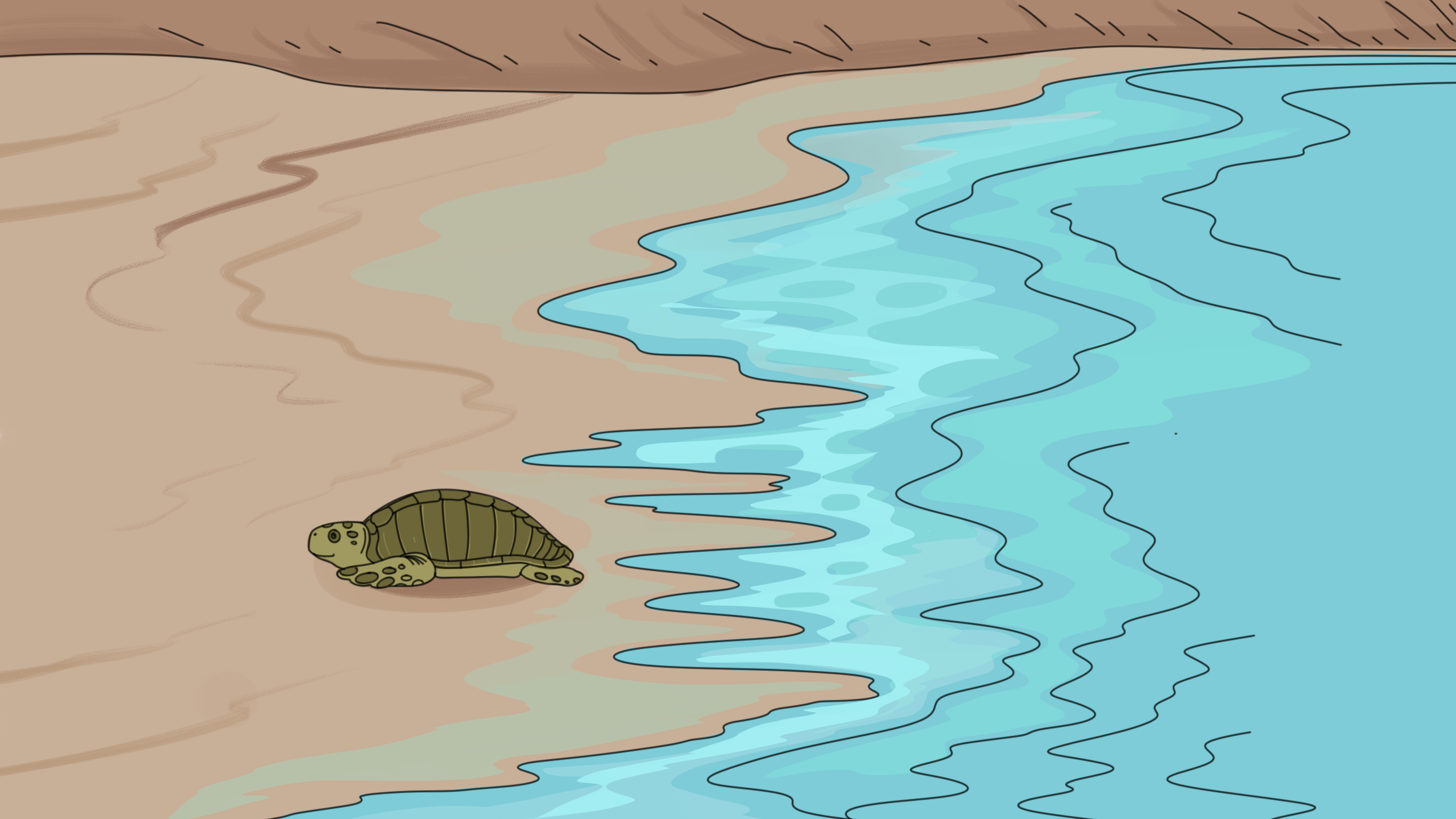

An Olive Ridley hatchling at Guhagar beach in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri district.

An Olive Ridley hatchling at Guhagar beach in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri district.

It's the eastern coast, particularly Odisha, that's considered the home of the Olive Ridleys. Here, every year, between January and March, the shores are witness to an incredible sight — thousands of Olive Ridleys coming together to lay eggs in what's known as arribada (Spanish for 'arrival'), a mass, synchronised nesting event that the species engages in. This year, a record seven lakh Olive Ridley turtles laid eggs at the Rushikulya rookery, one of the nesting grounds in Ganjam, Odisha.

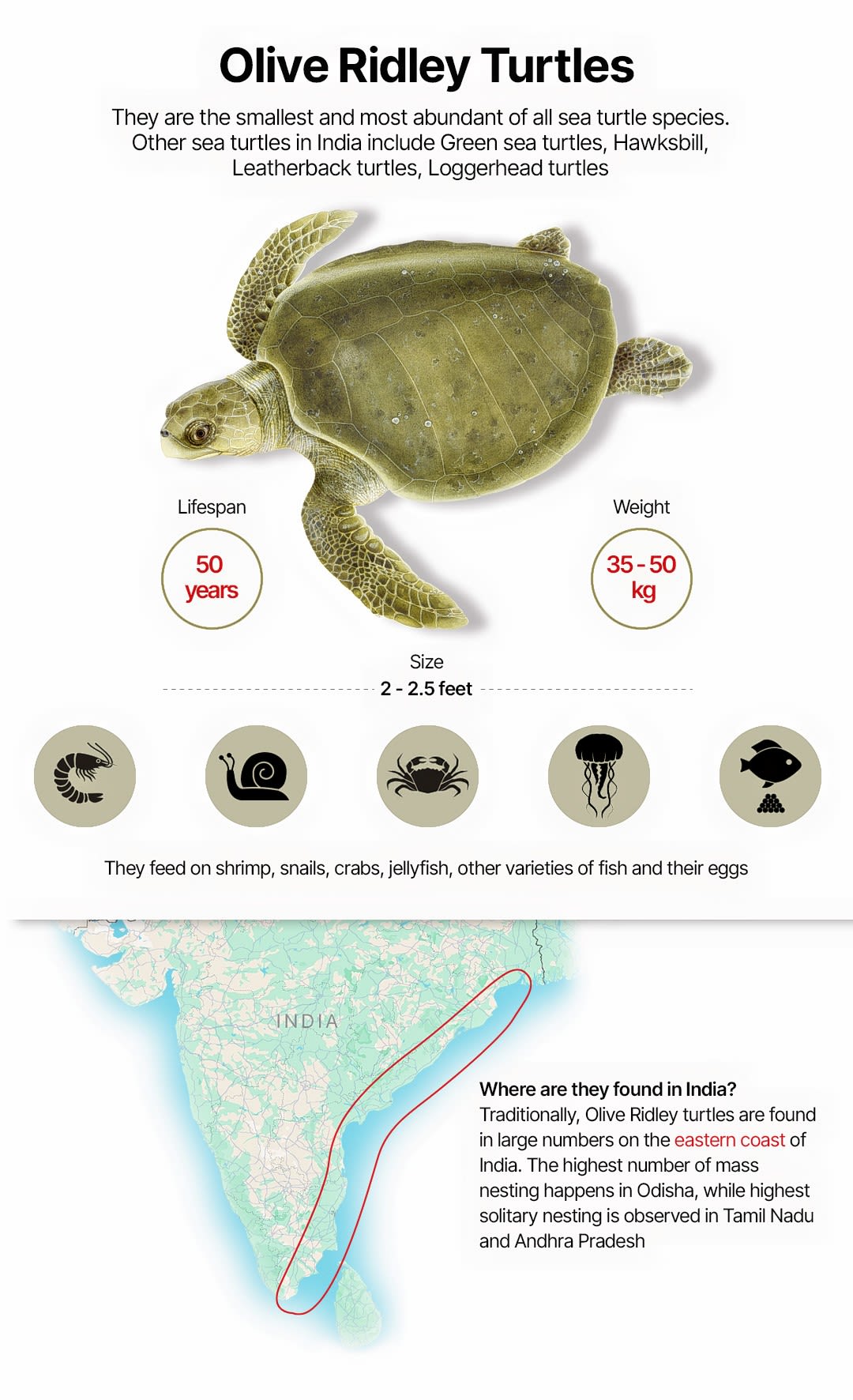

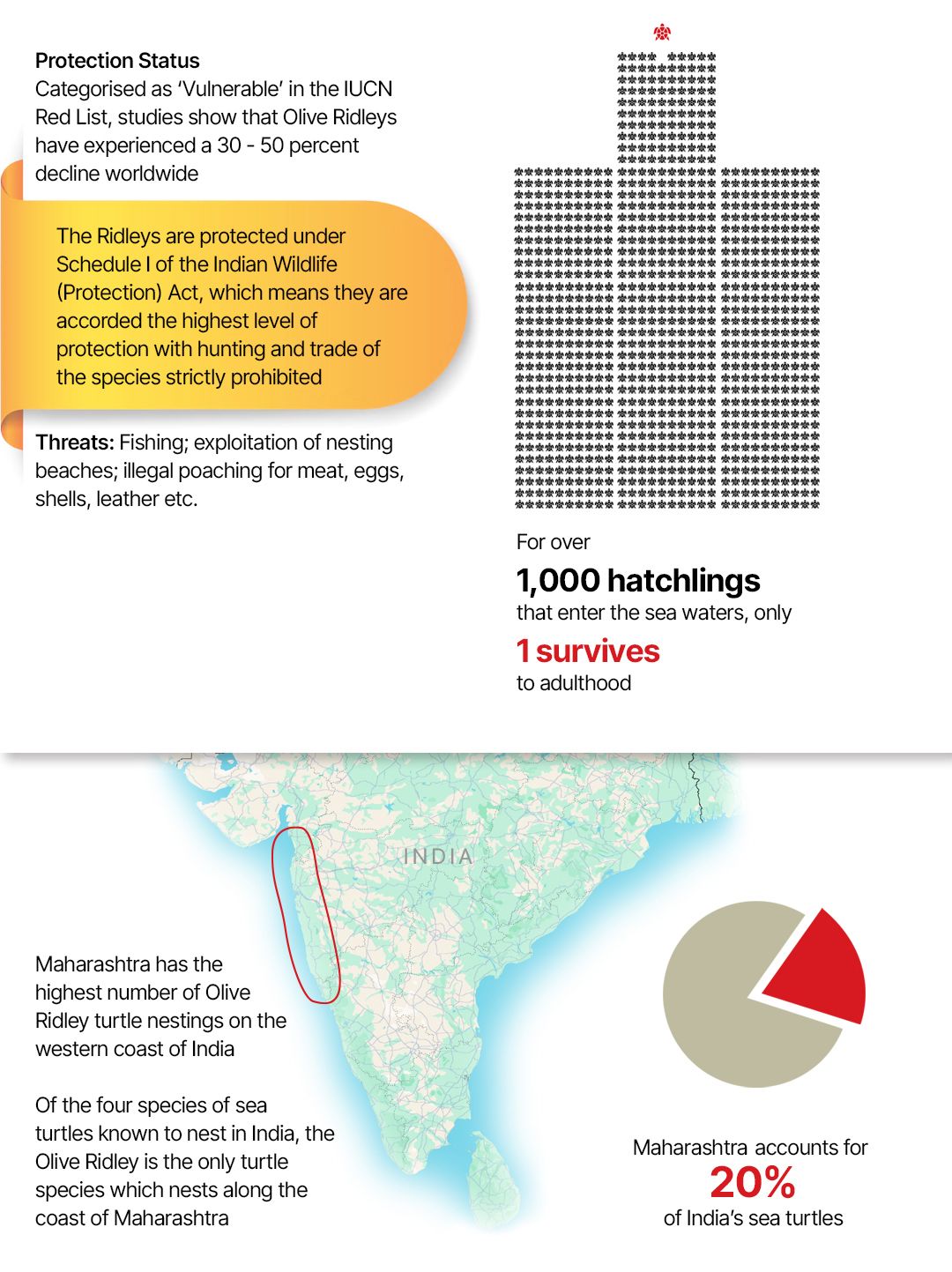

Yet, in India and elsewhere, the Olive Ridleys — despite being the most common sea turtle species in the world — have steadily dwindled owing to poaching and commercial fishing activities such as trawling, among other factors. The turtles have been listed as 'vulnerable' — facing a high risk of extinction — in the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List of Threatened Species. In India, they are protected under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. According to expert estimates, for every 1,000 hatchlings, only one Olive Ridley turtle reaches adulthood.

Which is why, the recent discovery of Turtle 03233 on Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri coast was a cause for cheer among the state's conservationists and Kasav Mitra Mandal, a 146-member cohort of ‘beach managers’ deployed by the Maharashtra forest department for a monthly remuneration to provide a safe nesting habitat for Olive Ridleys across three districts in the state.

According to the preliminary findings of a study by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the state forest department, Maharashtra, which has the highest number of solitary nesting sites along the west coast, accounts for nearly 20% of the country’s Olive Ridley nests. The study is slated to be submitted to the Union Environment Ministry in June this year.

"While the Olive Ridley numbers are much higher on the eastern coast owing to the geographical advantages, conservation efforts cannot be neglected on the west coast," says Kanchan Pawar, Deputy Forest Officer of the Maharashtra forest department's Mangrove Cell, South Konkan, which is leading the conservation efforts. "Sea turtles are the most important species in marine life as they play a crucial role in maintaining the fish population and aquatic biodiversity. These turtles primarily feed on jellyfish and sea algae. If turtle numbers decline, jellyfish and algae will thrive, thereby affecting the fish population."

It's a fact that Pawar's teams highlight during their workshops with coastal communities across Maharashtra. "Fishermen have now started realising that without sea turtles, not only will their existence be threatened, but their livelihoods will also be affected," says Pawar.

The Ridleys and the sea

As dawn breaks over Guhagar on April 26, the news of the birth of 33 Olive Ridleys spreads through the sleepy beach town like fire. Soon, a team of six ‘beach managers’ turns up at the beach. What happens next seems almost like a ritual.

As the newer beach managers drag their sticks across the dry sand to draw a huge boundary line, Dilip, 60, walks towards the coast. In his arms is a blue plastic tub full of sand and 33 wriggling Olive Ridley babies. Bending down, he releases the turtles one by one near the sea.

Guided by the vibrations of the waves and the light, the turtles, all of three-four inches, seem all too eager to rush home. As a crowd of spectators gathers around the boundary line and cheers them on, the hatchlings make a run for the ocean — clumsily at first, but with precision almost minutes later. While some touch the tideline within five minutes, others that end belly up are given a gentle nudge by their caregivers. In just 15-20 minutes, they become one with the ocean.

Beach manager Dilip walks towards the coast with a tub full of wriggling Olive Ridley hatchlings.

Beach manager Dilip walks towards the coast with a tub full of wriggling Olive Ridley hatchlings.

“It’s as if school has ended and now they are all running to go back home,” smiles Mohan Upadhye, a researcher with the state's Mangrove Foundation.

And then, just like that, the turtles learn to live in the waters — dodging predators and foraging for food — until they grow up over the next 10-15 years and it’s time for the females to nest. That’s when they’ll return to the shore they left as babies.

“Their lifespan of nearly 50 years is full of challenges. They get estranged from their nest siblings within minutes of birth. And then, there’s a lifetime of having to deal with natural predators, and of course, human activities such as fishing, trawling, rising pollution, plastic and other debris, oil spills etc,” says Upadhye, who is in charge of the beach managers and oversees the nesting-hatching process on the beaches of Ratnagiri.

Even before the turtles come to the shore, the beach managers launch into action to ensure a safe nesting experience — starting with the setting up of hatcheries. And once the turtles return to the sea after nesting, the beach managers ensure the eggs left behind are safely transferred to the hatcheries, where they await the arrival of the Ridley babies.

For the upcoming nesting season this year-end, the Maharashtra coast is expecting an influx of Olive Ridleys. Last year, Guhagar welcomed its first nesting Olive Ridley on November 15.

"The forest department deploys two beach managers for every 2 km," says Kiran Thakur, the Range Forest Officer of Mangrove Cell in Ratnagiri.

Kicking off their night patrol at 10 pm, when the beaches are free of human disturbance, the beach managers fan out until 3 am, after which they take a break. They then return to the coast at 5.30 am and continue the morning patrol until 7.30-8 am.

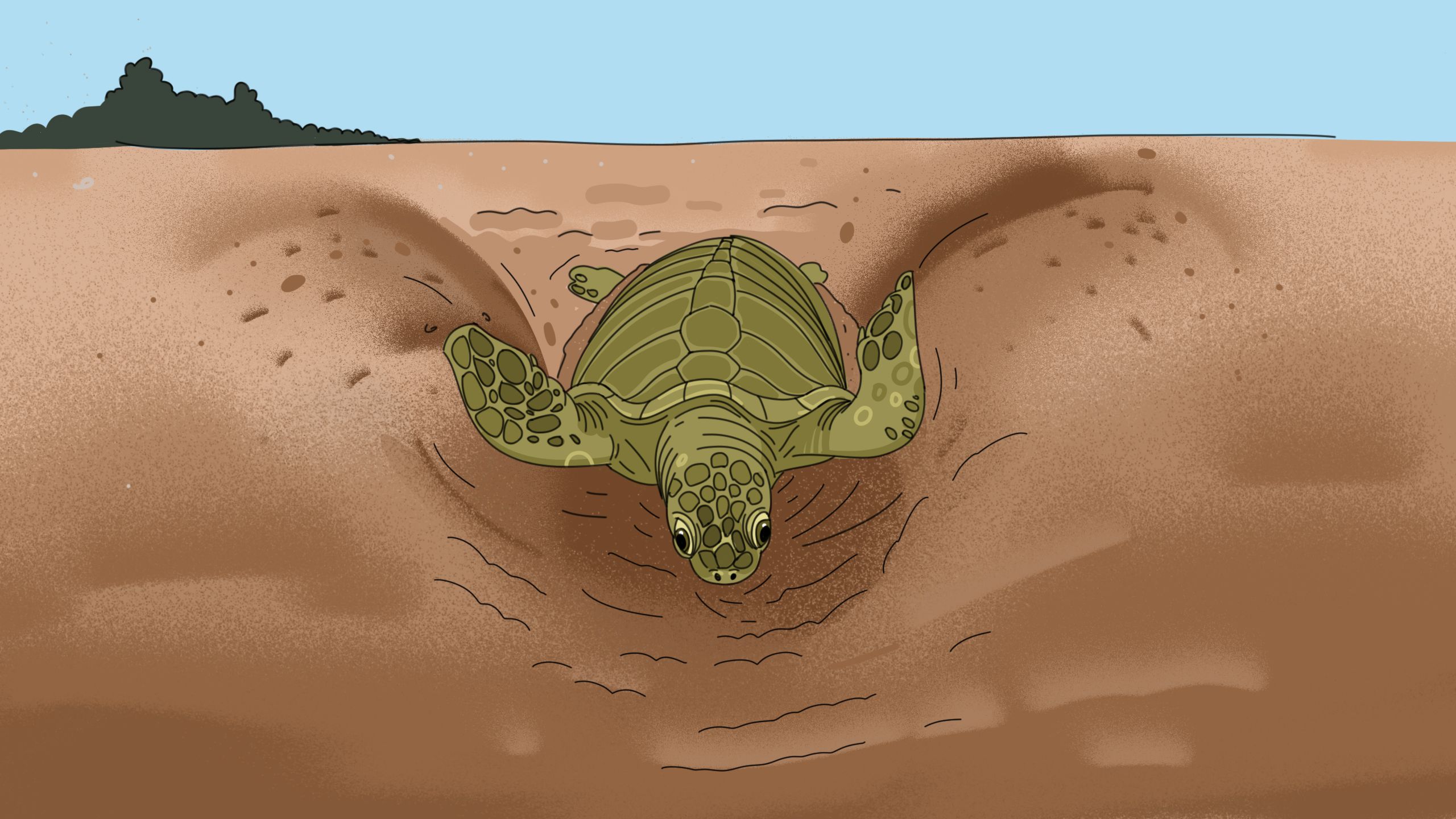

Upadhye said Olive Ridleys typically swim to the coast at night, seeking an ideal nesting spot — one that is away from the tideline and along a slope. After she finds a safe spot for her eggs, the turtle burrows the sand using her flippers to build a pot-like nest. Over the next two hours, the turtle lays anywhere between 80 and 150 eggs inside this nest, covers it hastily with her flippers and wades back into the waters. Left behind, these eggs must overcome a host of obstacles — predators, high tides and prying beachgoers and tourists — over the course of 45-50 days before they hatch naturally. Videos that surfaced on social media in March this year showed how attempts by female Olive Ridley turtles to nest along the Juhu beach in Mumbai were thwarted at least twice in two weeks. These videos showed curious visitors flashing their camera lights at the turtles and poking their shells.

Mohan Upadhye, a researcher with Maharashtra's Mangrove Foundation and in charge of the beach managers in Ratnagiri district, interacts with tourists at Guhagar beach.

Mohan Upadhye, a researcher with Maharashtra's Mangrove Foundation and in charge of the beach managers in Ratnagiri district, interacts with tourists at Guhagar beach.

As he releases the latest batch of hatchlings on April 26, a visibly emotional Dilip says, “We look after them as if they are our babies. If we lose some pillu (hatchlings) during the hatchling period, we get emotional.”

Vikrant Sangle, who was roped in as beach manager in 2022, agrees with Dilip. “Back when I first took up this work, I had no idea that such turtles would come and nest along our beaches. Pan hallu hallu avaad nirman zhala (Slowly, slowly, my interest developed),” he says.

“With each passing year, I have seen the number of nests and turtles grow. I believe that in some years we could even see mass nesting in our village, just like they see in Odisha,” he says.

Upadhye, who is from Velas village in Raigad district, says the conservation effort wouldn’t have been possible without help from villagers. “At times, we receive calls from residents alerting us about a possible nesting. They also prevent tourists from entering the hatcheries or disturbing the process of release,” he says.

The Nesting Process

Olive Ridleys are sea creatures and usually come to the shore only to nest. A female Olive Ridley lays eggs twice or thrice in a nesting season

During nesting, the female turtle looks for a safe spot on the shore. It uses its flippers to burrow the sand and build a pot-like nest. Over the next two hours, the turtle lays anywhere between 80 and 150 eggs inside this nest

It then uses its flippers to cover the nest with sand and then wades back into the waters

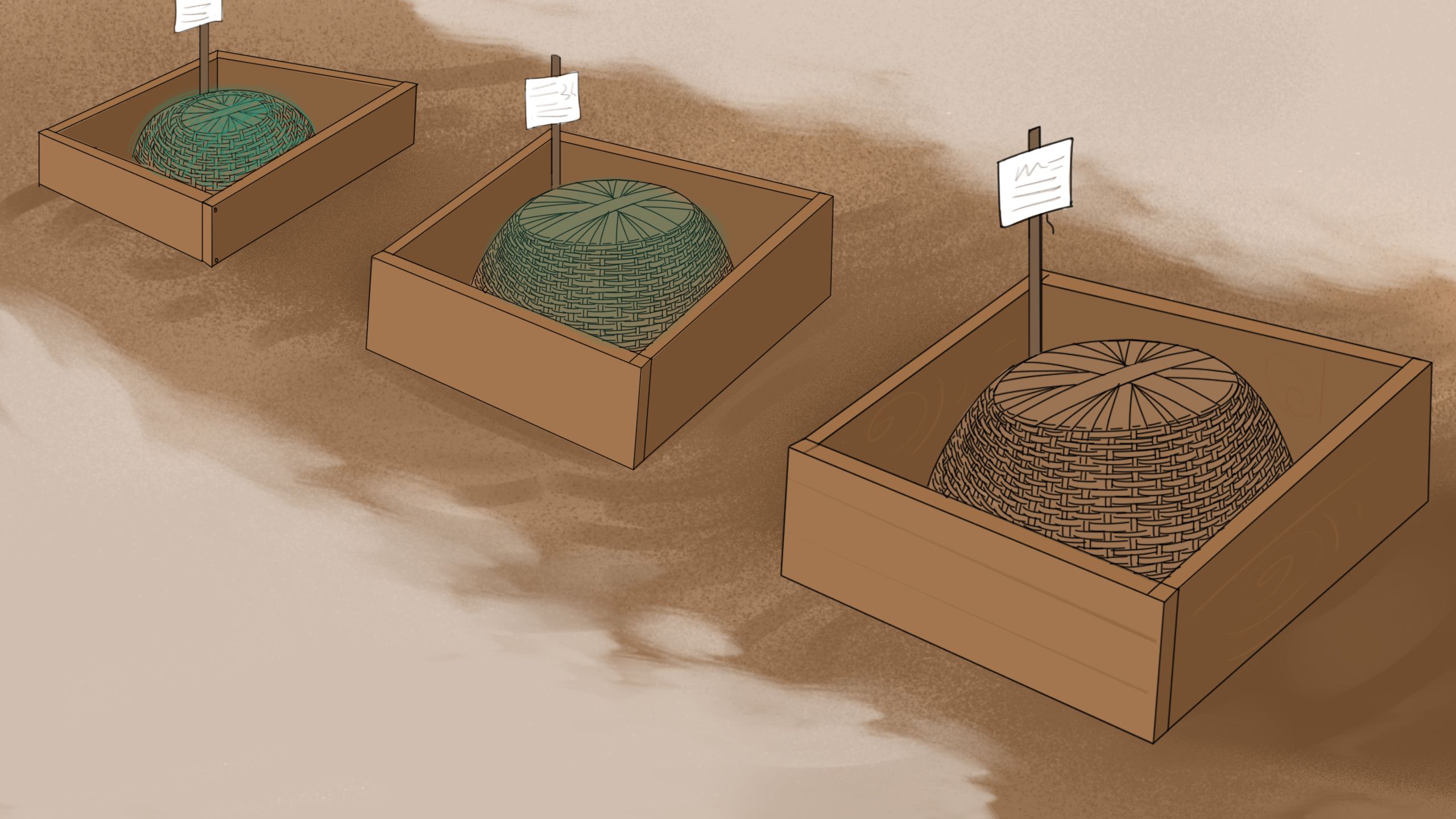

The Conservation

Volunteers, who protect the eggs from predators, extract the eggs and relocate them to a hatchery nearby, where a similar nest is dug up to mimic the original one. This process has to be done within two hours

The volunteers put a label on each nest with details of the number of eggs, date of nesting etc

The eggs hatch within 45-50 days, after which the hatchlings are released into the ocean

Friends of turtles

But not too long ago, these coastlines weren't the safest of spaces for the turtles.

Fisherfolk in the Konkan worship turtles as an avatar of Lord Vishnu — if a turtle gets entangled in their nets, they perform a puja seeking forgiveness, offer coconuts and apply kumkum (vermilion) on its shell before releasing it back in the sea. Yet, until some years ago, the local community was unaware that the beaches in their backyard served as a nesting site for these sea creatures.

Seventy-year-old Sanjay Shankar Bhosale, who was roped in as a kasav mitra in 2022 owing to his “knowledge of the coasts”, says, “I was born in Guhagar and have lived here all my life. Yet, I never knew that these turtles frequented our beaches.”

Upadhye, who has been working to conserve turtles for the past 21 years, says, “Until two decades ago, in several villages here, people would eat turtle eggs. Not just that, female turtles were poached and turtle meat was sold in the market.”

He says “true” change came only in 2002, when NGO Sahyadri Nisarg Mitra started awareness programmes along the coast. “In the survey, the NGO discovered that many villagers had no clue that the eggs on the beaches were of turtles,” he says.

The NGO, he says, started awareness drives to clear misconceptions and would often call on villagers to witness the hatching process. Slowly but surely, things started to change. “In some villages of Sindhudurg district now, villagers say that since the female turtle has returned to her maika (maternal house) to give birth, they should look after her babies,” says Mohan, who joined hands with the NGO in 2003.

By 2006, the Maharashtra government stepped in, with the forest department, in association with its Mangrove cell and local NGOs, including Sahyadri Nisarg Mitra, launching its Kasav Mitra or 'Friends of Turtles' programme.

The conservation programme roped in villagers for a monthly pay of Rs 13,000 as beach managers across 64 coastal towns in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri, Raigad and Sindhudurg districts.

Fisherfolk in the Konkan worship turtles as an avatar of Lord Vishnu.

Fisherfolk in the Konkan worship turtles as an avatar of Lord Vishnu.

Shardul Todankar, 22, a second-generation beach manager, says his knowledge of turtle nesting came from his father Alhad Eknath Todankar, among the first beach managers in these parts. “He has looked after turtles and their nests since 2013. At 3 am every day, he would patrol the beach. Though he usually covered the entire beach all by himself, I would join him at times. That is how I learnt about turtles and grew fond of them,” says Shardul, a BCom student, who decided to do the job after his father passed away in 2021.

It's “nasha (addiction)”, says Abhinay Kelaskar, 36, a resident of Anjarle beach town and a Mangrove cell researcher, about his fascination for turtles. “Normally, I wake up around 7 am. During the nesting season, I automatically wake up at 4 am and head towards the sea. The excitement I feel is inexplicable. In fact, at times, I even dream of turtles.”

The project has begun to show results. Over the past two years, the number of eggs laid by nesting Olive Ridleys across Maharashtra has seen a 75% spike – from 1.57 lakh eggs in 2022-2023 to 2.77 lakh in 2024-2025. So have the number of hatchlings — 1.25 lakh hatchlings released so far this season, against 84,251 hatchlings in 2022-2023.

In fact, Olive Ridleys have also made a comeback at Kihim beach in Alibaug, a popular beach town 100 km south of Mumbai, for the first time in 40 years. Around 70 hatchlings were released into the sea at Alibaug on April 26 this year.

The project has also provided a new source of livelihood for the villagers — in these coastal towns of Konkan, fishing and cash crops such as mangoes are the primary sources of income.

For the tourists who frequent these beaches, the turtles are an added attraction. Since 2006, Velas and Anjarle towns in Ratnagiri district have been celebrating Olive Ridley festivals.

Clumsy hatchlings that end belly up while on their way to the tideline are given a gentle nudge by a caregiver.

Clumsy hatchlings that end belly up while on their way to the tideline are given a gentle nudge by a caregiver.

A long journey ahead

Despite the positive trends, scientists, including Dr Suresh Kumar, senior scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, who has studied the movements and migration of Olive Ridley turtles as part of his doctoral research, say it's a long road ahead for the vulnerable species.

"While it is essential to highlight the growing number of nesting sites, I would be hesitant to say that the population of Olive Ridley turtles is also growing, as a large number of turtles are still dying,” Kumar says.

DFO Pawar agrees, adding that conservation work in Maharashtra is in its early stages. Yet, she is hopeful that the efforts will pay off some day. "It is possible that some of the hatchlings we released from our coast 10 years ago are now returning as adult females to nest," smiles Pawar.